The late soprano Maria Callas as Violetta in Verdi’s La Traviata

A good while back, I published a blog entry devoted to “Three Titanic Tenors: Mario Del Monaco, Franco Corelli, and Richard Tucker” (see the following link: https://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2012/07/29/three-titanic-tenors-del-monaco-corelli-and-tucker/). Three singers who just happened to have been some of my favorite male artists from my past. But after some prudent soul-searching and thoughtful deliberation, I felt the time was ripe – MORE than ripe, I should say – for another one of those surveys of the best and brightest stars from the annals of performances past.

Today, my subjects are the women of opera, those so-called prima donnas – or better yet, the “first ladies” of song. They were the artists most attuned to the skill of belting it out to the rafters. Indeed, they are the First Ladies of Opera. As such, we will feature three of the most prominent and influential women artists, outside of dear old mom (sans the apple pie, of course) of my early musical life; the ones that I and many liked-minded fans of the genre have grown up with, listened to, and admired from afar — time and time again.

In short, a vocal triad of the most cherished soprano voices I know of; an earthly trinity of now heavenly divas. Well, maybe not so heavenly all of the time but established performers nonetheless, ones that were guaranteed to send shivers up and down one’s spine.

And here they are, in print and in sound, ready and willing to regale us with their lustrous tones: the Greek American Maria Callas, the Italian Renata Tebaldi, and the Czech-born Zinka Milanov.

Why these specific singers, you may ask, from among the dozens, if not hundreds of choice exponents? The answer is quite simple: theirs were the most frequently recorded voices of the decade between the years 1949 and 1959 (and a bit beyond) during the heyday of long-playing records, those of the two-and-three-disc variety of complete (or nearly complete) operas.

Captured for all time by the three most familiar classical record labels of the period: EMI Odeon/Angel, Decca/London, and RCA Victor — with a few minor stragglers along the way — this tempestuous female triumvirate left behind a recorded legacy unlike any that has come before or after them.

At this point in my essay, it’s best to let the artists “speak” for themselves, or rather sing if you get my drift.

Maria Callas in a photo shoot

The Divine in All of Us

It is nonetheless fitting that we begin with the youngest of our hallowed group, La Divina (or “The Divine One”) herself: The incomparable Maria Callas. Sad to say, Callas was also the first of this all-star lineup to have passed into operatic legend, and at the earliest of ages.

Readers should make note that December 2, 2023, marked the one hundredth anniversary of Maria Callas’s birth, which we are observing today, albeit belatedly. Despite the normal ups-and-downs of an international career, especially one marked with more than its share of controversy, today the Divine One’s recorded legacy – and the myth that surrounded her as an artist of the front ranks – continues to enjoy celebrity status among connoisseurs of fine vocal music. Perhaps more so now than at any other time.

As an individual and a performer, even as a vocal coach of note (for instance, as she was portrayed in Terrence McNally’s Tony Award-winning play Master Class), one can state with absolute assurance that most such artists, conductors, stage directors, managers, impresarios, even those remotely connected to the operatic art itself, have claimed affinity for and derived untold inspiration from this legendary singer.

Born in Manhattan, on December 2, 1923, Maria Callas, christened Maria Anna Sofia Cecilia Kalogeropoulos, which her Greek-born father shortened to Kalos (and later to just plain Callas, with minor variations in between), spent her formative years in New York’s Big Apple and in Astoria, Queens – that is, up until the age of fourteen.

As a result of her parents’ bickering and subsequent separation, Callas immigrated back to Greece in 1937, along with her mother and older sister. The mother, being your typical Old-World matriarch, insisted that both daughters receive a musical formation as well as a “normal” one. That Maria took full advantage of this golden opportunity to shine marked her as a sensitive individual able to discern what talent had laid dormant within her at the time.

The presence in the Greek Isles of Spanish soprano Elvira de Hidalgo, who became Callas’s first teacher, was a consequence of the upheaval brought on by the Second World War. With that, the official start date of the young singer’s vocal studies took place in 1939; a venture that, in the words of several annotators, became “formative” to her development as a viable artist, one with an extraordinary insight into her roles that comprised a rare ability to shift between both standard and bel canto repertory with equal flexibility.

Elvira de Hidalgo (left) with her former pupil, Maria Callas

Still, it might have been better for all concerned had Callas and family remained in the U.S. Doubtless, the reality of life in war-torn Europe and the consequent Aegean Sea area grew ever more hazardous for inhabitants and foreigners alike. With her having faced famine, financial difficulties, humiliation, and material deprivation, young Maria nevertheless overcame these challenges by sheer force of will if not determination – what choice did teenaged girls, and their fellow Grecians, have?

Keeping the above situation in mind, Callas’s earliest operatic experiences would take place at the Greek National Opera in Athens, between 1939 and 1945, with early appearances in a variety of roles (La Gioconda and Leonore in Fidelio among them) that encompassed a vast range of styles and challenges. Critics at the time lauded the singer for possessing a “crystalline voice” and a “rare sense of theatricality.” Unfortunately, few if any recordings or film footage exist from that formative period, which limits anyone’s interest in further researching her operatic activities during wartime.

Luckily for admirers, today’s listeners are indeed fortunate to have subsequent evidence at their disposal, mostly from her catalog of EMI/Angel studio recordings, along with rare video extracts, photographs, and/or privately held (or “pirated”) performances, many with below average sound quality. Still, the best of these highly suspect releases revealed a readily formed artist, one of astonishing range and temperament, with as complete a mastery of the dramatic arts that, in most cases, far transcended the limitations of the era.

Unfortunately, throughout the years and certainly after her untimely passing, the part that most readers and reviewers have been forced to confront regarding the Callas legacy – and that interviewers and documentary film producers have touched upon for decades on end – are the salacious rumors and offstage activities associated with celebrity scandals.

These are not the sort of memories, mind you, that your average audiophile would like to take away from. Nevertheless, it’s what fans long associated with La Callas have come to accept and put up with on a regular basis.

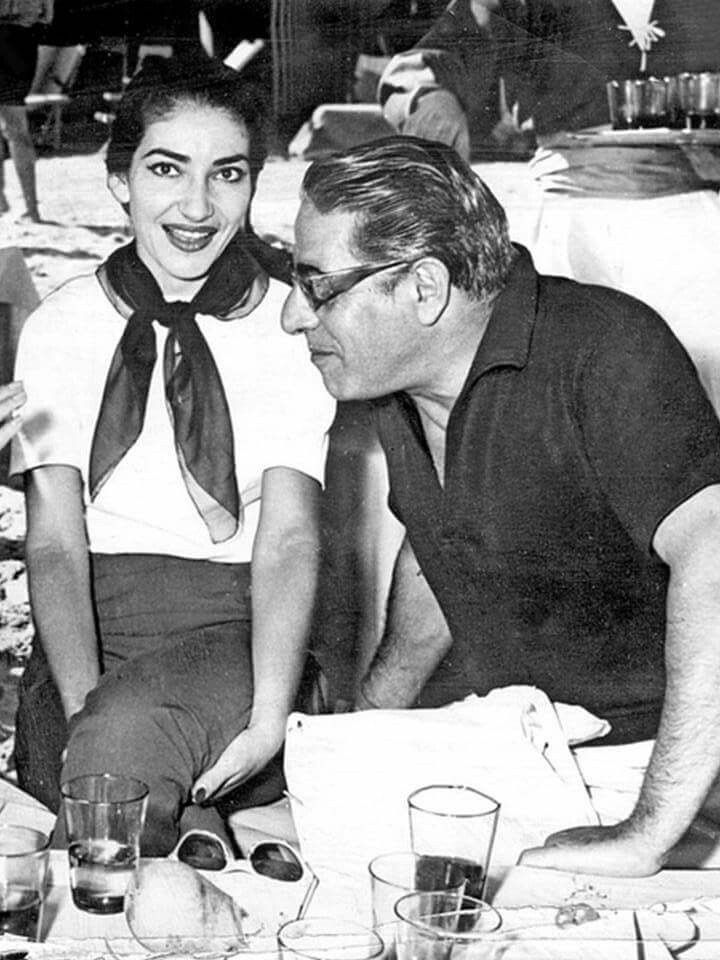

Love On the Rocks

Almost certainly her marriage to the much older Italian industrialist Giovanni Meneghini (which earned Callas her middle name as advertised on billboards and record labels from her La Scala, Milan period) and subsequent liaison with Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis, which later blossomed into a purported “rivalry” of sorts with JFK’s widow Jacqueline Kennedy (exaggerated, to a degree, by those ever-present paparazzi), shifted the focus away from the singer’s theatrical and recorded accomplishments. These incidents may remind readers of what Lady Diana Spencer once had to go through.

Callas with shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis (ca. 1960s)

Another such narrative relates to Callas’s fraught relationship with the Metropolitan Opera. Ira Siff, that peripatetic radio commentator and multi-talented writer, singer, and vocal instructor, has gone into excruciating detail, in the December 2023 issue of Opera and Opera News, about the correspondence and communication, both in writing and via interpersonal means, between Madame Callas and then-Met Opera General Manager Rudolf Bing’s efforts to bring the artist to the New York stage.

According to Mr. Siff, Bing first heard about Callas in or about the year 1949. Their back-and-forth interaction, as documented in the article “ ‘Love, Maria’: Ira Siff on Callas’s Relationship with the Met,” seemed not to have been as acrimonious as originally thought. A miracle in itself, when you consider his and her reputations at the time.

As a matter of fact, Bing displayed a sort of grudging respect if not outright admiration for Maria and was indeed willing to have her appear with the company given her exorbitant monetary demands. Bing was thwarted in his efforts, however, not only by her insistence on more challenging projects – with, by the way, as little rehearsal time as possible – but those of her meddling husband, Signor Meneghini (mainly of a financial nature).

One such assignment, that of the villainous Lady Macbeth in Verdi’s Macbeth (a first for the Met) unfortunately fell through the cracks and would ultimately be taken over by debuting Austrian soprano Leonie Rysanek, to her eventual good fortune.

Despite the Met’s loss, the gain was with record collectors and serious vocal addicts, who could hear something of what they had missed in several live extracts (from 1952) of the aria “Vieni, t’affretta.” In these remarkable examples, Callas displayed a thorough command of the Verdian and bel canto idiom, with trills and prodigious leaps and bounds up-and-down the scale; the kind of hard-to-define vocalism that clearly describes Lady Macbeth’s malevolent character as much as it eschews show-stopping excitement for theatrical effect.

If ever there was an artist who fully captured Verdi’s directive that the singer of this part employ “an ugly voice, a suffocated sound,” with the last note of the Sleepwalking Scene to be taken “as a thread of voice,” then Callas was the perfect candidate to have carried out these instructions to the letter. Few singers of this part, then and now, have shown as much capacity to deliver that disembodied, otherworldly aspect that Verdi called for as had Callas, one that marked Lady Macbeth as a distinctive addition to this and every other soprano’s repertoire.

Coincidentally, it was around this time, between the early to mid-1950s, that Callas famously shed nearly 80 pounds of weight which, if one can believe the pundits, may or may not have altered the general sound and scale of her phenomenal vocal apparatus. The weight loss certainly lent much-needed glamour to her stage deportment as well as boosted her confidence level.

Photos taken at the time give the impression that Callas was being groomed to challenge Audrey Hepburn for the cover of LOOK Magazine. For better or for worse, it made Maria one of the world’s most sought-after photographic subjects – one ripe for the gossip columns.

Maria Callas as a Parisian fashion plate

In addition to her newfound celebrity status, the singer’s association with such contemporary stage and film veterans as the Italians Luchino Visconti, Franco Zeffirelli, Nicola Benois, and Pier Paolo Pasolini gave renewed impetus to the notion of Callas as the “jet-set” prima donna of choice.

Regardless of the notoriety, none of these distractions should detract serious listeners from engaging with Callas through her countless recordings, in particular her recitals from the French repertoire ( a personal favorite of mine), a language she was completely at home in, along with Italian, English, and, of course, her native Greek.

A minor sampling of items from her vast recorded legacy surely must include a live 1955 stage performance from La Scala of Violetta Valery in Verdi’s La Traviata, directed by Visconti, with colleagues Giuseppe Di Stefano, Ettore Bastianini, and conductor Carlo Maria Giulini.

Honorable mention should go to her ferociously delivered “Divinités du Styx!” from Christoph Willibald von Gluck’s baroque opera Alceste, the same composer’s equally hypnotic “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice,” from Orphée et Eurydice, the seductive “Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix” from Camille Saint-Saëns Samson and Delilah, and, of course, her traversal of the title part in a complete Bizet’s Carmen, phrased in impeccably accomplished French and enacted with the fire and gusto of a lioness defending her turf.

Most of the above recordings were made in the early to mid-1960s. From then on, Callas’s voice steadily diminished in amplitude and fullness. Those new to the singer might have experienced the sense of three different voices trapped in a single body: a piercing top tone, followed by a hollower middle section, and ending with a powerful low register.

Some say that too many years of singing the “wrong repertoire” (whatever that meant) were to blame; that too much and too sudden a weight loss contributed to her vocal decline; or that overly and/or artificially “coloring” her voice only accelerated her premature retirement from the stage. The issue remains debatable, even to this day.

Another of her most admired roles, that of the flamboyant diva Floria Tosca, can be viewed with intense interest via the Second Act staging from a taped 1964 performance at London’s Covent Garden costarring another of Callas’ frequent stage and recording partners, the baritone Tito Gobbi as Baron Scarpia. This is the famed production where two artists of equal dramatic and vocal stature challenge each other to heights few others have attained.

During their brief confrontation and battle for the life of Tosca’s lover, Callas throws herself at the villain in a vain attempt to get her way. Too quick for her, the wily Scarpia grasps at Tosca by the wrists while spreading her arms out in a crucifixion-like stance. “That was Maria!” was Gobbi’s written assessment of this seemingly unrehearsed yet totally spontaneous inspiration. Simply marvelous!

Vocally, Callas’ interpretation of the aria, “Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore,” (“I live for art, I live for love”), is anticlimactic in its way to the foregoing, no matter that the singer’s vocal line turns squally and uneven at the piece’s climax. Still, looking at it from the character’s perspective and from what the composer Giacomo Puccini expected of any artist, Maria gave a much-needed touch of vulnerability and pathos to the moment that, in lesser hands, can seem obvious or insincere.

Life After Death

Personally, I like to believe that after Callas’ failed marriage to the avaricious Meneghini; her on-again, off-again affair with the womanizing Onassis; her close friendships and (let’s face it) professional liaisons with some of Italy’s finest directors (resulting in an unfortunate debut in Pasolini’s desultory filming of Medea), in addition to her final mid-seventies concerts with frequent stage and recording partner Di Stefano, may have caused her to experience a fundamental loss of self-confidence.

If such things were possible back then, one might have envisioned a major career change for Callas by the planting of her feet on the Broadway stage: What a thoroughly demented Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire she might have made, or for that matter what a potent Mama Rose in Gypsy! Can you imagine what she might have done with Mrs. Lovett in Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd? The possibilities seemed endless and were to die for, but alas were never meant to be.

That Callas has remained popular, despite the many obstacles and turnarounds in her career, stands as a tribute to her durability as both a singer and an artist of the people, and not just for the cognoscenti. A conservative, unofficial estimate of her fandom would surely number in the millions – of that, we have little doubt. In her followers’ minds, she remains divine.

Maria Callas passed away of a heart attack, in Paris, on September 16, 1977. At the time of her passing, Callas was alone and unattended. She was only 53.

Last known photograph of Maria Callas in Paris, ca. 1977

RECOMMENDED RECORDINGS:

Maria Callas:

- Aida (Barbieri, Tucker, Gobbi, Zaccaria, Modesti – Serafin) EMI/Angel

- The Barber of Seville (Alva, Gobbi, Ollendorf, Zaccaria – Galliera) EMI/Angel

- Carmen (Gedda, Guiot, Massard – Prêtre) EMI/Angel

- Lucia di Lammermoor (Di Stefano, Gobbi, Arié – Serafin) EMI/Angel

- Medea (Scotto, Pirazzini, Picchi, Modesti – Serafin) Mercury/Foyer

- Norma (Ludwig, Sutherland, Corelli, Zaccaria – Serafin) EMI/Angel

- I Puritani (Di Stefano, Panerai, Zaccaria – Serafin) EMI/Angel

- La Sonnambula (Monti, Zaccaria – Votto) EMI/Angel

- Tosca (Di Stefano, Gobbi, Luise – De Sabata) EMI/Angel

- La Traviata – The “Lisbon Traviata” (Kraus, Sereni – Ghione) EMI/Angel

(To be continued….)

Copyright © 2023 by Josmar F. Lopes

One thought on “They Lived for Their Art — The First Ladies of Opera: Callas, Tebaldi, and Milanov (Part One)”