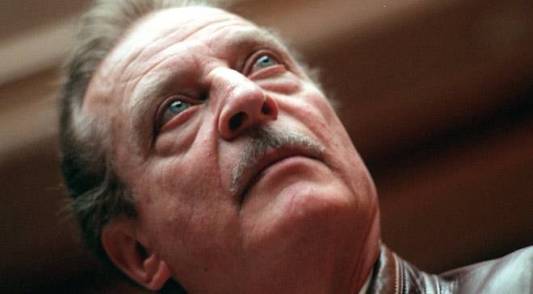

Charlton Heston as Moses in ‘The Ten Commandments’ (Paramount Pictures)

Staffs that transform into snakes. A sea that opens up to allow people to pass through, and then collapses to swallow an entire army. Flames that shoot up from the ground, which thrust themselves into the side of a mountain so as to trace the outline of two stone tablets — tablets that miraculously become the manifestation of God’s law.

Is this some punch-drunk producer’s vision for a potential pop star’s debut, or an archival clip from the Iraq War? Neither, to be exact. This is the story of Old Testament prophet Moses, the flight of the Hebrew slaves from Egypt, and the giving of the Ten Commandments. And what a marvelous kitsch classic Cecil B. DeMille’s religious epic is! No other film of the fifties has come close to capturing its size, scope, gaudiness, and spectacle — or been such a perennial favorite on network television — as The Ten Commandments. Indeed, only a handful of religious films have been treated with such a heady mixture of familiarity and contempt as this picture has.

For a work purportedly based on the “Holy Scriptures and other ancient and modern writings,” there are enough over-the-top performances in it to place The Ten Commandments at the foot of the altar of all-time campiest movie ever made — with a much bigger budget, of course. Considering its weighty subject, there’s a seriousness of purpose and execution few epics of the period could match. It stands as a worthy monument to all that was good and bad in Hollywood around the year 1956. Not only does it accurately portray American society as it was during the postwar era, but it also suggests what that society would become in the turbulent years that lay ahead.

In view of this, it’s a film firmly rooted in fifties popular culture and the prevailing political trends, when America’s morals and values were being put to the test as the result of tremendous external and internal upheaval. The impact this work has had on movie audiences of the time can be measured in its visual interpretation of various aspects of 1950s life, balanced against how those same aspects are viewed today.

Conflicts and Hostilities

Among the many external forces at play were the recently concluded Korean conflict and the resultant tensions it brought about. This situation helped put the Cold War mentality into place, which became an integral part of American life, and made abundantly evident, as The Ten Commandments was being readied for production.

Major events of 1956, such as the presence of Russian tanks in Hungary, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s program of de-Stalinization and his enthusiastic support of nuclear proliferation and competition with the West, all helped to define the ethos of that era. In the Middle East, Arab-Israeli tensions had reached their height in July of that year, as Egypt closed off access to the Suez Canal. Then, in October, Israel invaded Egypt, the land of its former oppressors, thus ending years of passive resistance to Arab hostilities and forming an ironic coda to the movie’s message of freedom from servitude.

At home, former Army general Dwight D. Eisenhower easily won re-election as president, with America maintaining its status as the most powerful and prosperous nation on earth — not unlike ancient Egypt in its day. But all was not as it seemed. The country had just undergone a particularly prickly period of political instability and cultural uncertainty, what with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings, the McCarthy-Army Communist witch hunts, and the seemingly innocuous introduction of rock-n-roll to the nation’s teens.

These issues would manifest themselves, both subtly and overtly, in the on-screen clashes between the hapless Hebrew slaves and their abusive Egyptian taskmasters — and be brought to vivid life as part of the movie’s main talking points.

Controversial Productions

Hollywood was by no means immune to these concerns, as it continued to exploit the mass market for movies to its fullest. New and controversial productions were being pushed to the front of the cinematic assembly lines, many with startlingly adult subject matter for the time.

Some of the more, shall we say, out-of-the-way items introduced themes associated with out-and-out racism (Giant, The Searchers), corporate ladder-climbing (The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit), Freudian pop psychology (Forbidden Planet), suburban conformity and loss of identity (Invasion of the Body Snatchers), deterioration of the family unit (The Man Who Knew Too Much), virgin child-bride seduction (Baby Doll), latent homosexuality (Tea and Sympathy), manic depression and self-mutilation (Lust For Life), cowardice and connivance during battle (Attack!), and impotence, promiscuity, and out-of-wedlock pregnancy (Written on the Wind).

These and many other films represented an extreme departure from the usual Saturday afternoon escapist fare. Fostered by postwar anxiety, years of pent-up frustrations, and lack of suitable outlets for those same feelings, they were the studios’ biggest arsenal in the continuing battle being waged for prime-time viewer attention — a battle being won by television. Audiences en masse preferred to sit it out on the sidelines rather than leave the comfort and control of their cozy abode.

The movie capital addressed this malaise with bigger and wider — though not necessarily better — screen fodder. In the process, it created or perfected such innovative techniques as Cinerama, stereophonic sound, CinemaScope, 3-D, Todd-AO, and VistaVision. In sum, it was striving mightily to bring to the neighborhood cinema something the average viewer couldn’t get by reclining in his Lay-Z-Boy.

For a religious film to hope to compete with the pulse of the pictures captioned above, it would have to be in the vein of something extraordinary.

Master Showman

Young Cecil B. DeMille (Paramount Studios)

Enter Cecil Blount DeMille, Paramount Pictures’ cinematic savior of the moment. As one of Hollywood’s greatest living showmen, DeMille was widely regarded as a motion-picture founding father. The son of an Episcopal lay minister and amateur playwright, with close ties to famed Broadway impresario David Belasco — and a reputable stage actor, to boot — DeMille was known for his wide canon of religious and historical epics.

His films were fairly elaborate affairs, all sharing a central theme or idea, i.e., that of the fallen man or woman redeemed by the power of love, a long dormant patriotic fervor, or a newfound spiritual conversion. They were moralistic, preachy, simplistic, and, perforce, unsubtle works.

They were also huge money-makers for the home studio, mostly by skirting the boundaries of decency due to their surprisingly open portrayal of sexuality and sadism, a conscious influence from DeMille’s theatrical background and repressed Victorian upbringing. He was fond of saying to his screenwriters that “you can’t show the wages of sin without showing the sin.”

Some of his earliest explorations into the religious realm include the first film about the Maid of Orleans, Joan the Woman (1915), with American soprano Geraldine Ferrar as Joan of Arc; the silent version of The Ten Commandments (1923); the independently produced The King of Kings (1927); the Romans vs. Christians saga, The Sign of the Cross (1932); and the starchy Richard the Lion Heart spectacular, The Crusades (1935).

DeMille had previously brought to the screen his lavish production of Cleopatra (1934), with Claudette Colbert as the comely seductress and a young Englishman named Henry Wilcoxon as Marc Antony. After the critical failure of The Crusades, however, he abandoned outright religious depictions for a time in favor of more accessible historical fare. By 1954, after having churned out two back-to-back blockbusters for Paramount — the first, Samson and Delilah (1949), was a pseudo-serious study of the biblical strongman from the Book of Judges; and the second, The Greatest Show On Earth (1952), a big-top extravaganza which won the Oscar for Best Picture — DeMille found his former popularity on the wane.

For years, audiences had flooded him with queries as to when, if ever, he would remake his silent classic, The Ten Commandments. At 73, the veteran director knew his kind of cornball, crowd-pleasing pictures were going out of style. Consequently, he desperately yearned to please his public one last time by capping his long career off with a spectacle that was second to none. It would have to rival the very best that Hollywood had to offer. Toward that end, he spent the then-princely sum of $13 million dollars — the first time he had ever gone over-budget on a project — on his widescreen, Technicolor rehash of the story of Moses and the Hebrew Exodus.

Obsession with Authenticity

Although most of the new picture’s interiors would be shot on the sound stages of Hollywood and Paris, many of the big outdoor scenes were filmed “on location in Egypt, in the surrounding desert country of Shur and Zin, and on the very slopes of Mount Sinai” itself.

Two years before filming began, DeMille sent legions of researchers off to scour the world’s libraries and museums for relevant data concerning arms, weapons, costumes, makeup, and other paraphernalia used by the people of that ancient epoch. It had been a regular routine of his to prepare for each facet of production prior to actual shooting. And this film was no exception. No doubt the tremendous potential for worldwide receipts fanned DeMille’s normally obsessive pursuit of authenticity to even greater heights, with the added knowledge that an audience familiar with the subject of Moses and the Exodus would be looking even closer for any inherent flaws in this well-told tale.

To counter any prospective arguments that would seriously hamper the profitability of his greatest achievement — and as a nod to the keepers of the morality flames — DeMille had clergymen from the major Christian, Jewish, and Islamic faiths critique the film for accuracy, among other concessions. These steps were all in keeping with his grandiose scheme for making his latest edition of The Ten Commandments as reverent and respectable a work as possible, as well as a box-office bonanza.

Tyrant and Patriot

In a rare, on-screen appearance before the movie proper, DeMille steps out from behind the curtain to announce the principal theme of his work: “Should men be ruled by God’s law or be ordered about by the whims of a dictator? Are they the property of the state or free souls under God?”

DeMille in the on-screen Prologue to ‘The Ten Commandments’

These were mighty sentiments back then (more so, in today’s troubled times). Coming as they did from a man viewed by many as a hard-driving, humorless taskmaster, they were even more disturbing. Critics compared DeMille’s tightfisted style behind the camera to the dictatorial whims of fellow Austrians Erich von Stroheim and Fritz Lang, both famous for their iron-gripped authority and exaggerated demands upon cast and crew. That the aristocratic DeMille loved to work in jodhpurs and riding boots, with riding crop at his side — and kept several lackeys employed just to fetch his chair and megaphone — did nothing to dispel that image nor endear him to his minions.

Despite his formidable reputation, however, DeMille could be tolerant toward his troops, especially around the holidays. But tyrant or not, the director’s movie message was made abundantly clear: The land of liberty had no place for rigid rulers with militaristic ideals, even if Hollywood’s own moguls failed the acid test.

DeMille’s staunch anti-New Deal Republicanism was evident throughout much of the Depression and intervening war years, a time when a growing number of Americans denounced President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a fascist. Along with directors Frank Capra, George Stevens, and John Ford, DeMille had done his bid to promote U.S. wartime propaganda by producing the long-winded Story of Dr. Wassell (1944), a stodgy, patriotic ode espousing courage and honor in the face of a growing oriental threat. No one could provide movie patriotism better than DeMille, when he put his mind to it.

With the Cold War having frozen relations with our former Russian allies, DeMille felt The Ten Commandments could resurrect the idea of our going back to an earlier, simpler time, when the world could be made safe again from opposing (read: Communist) viewpoints, if only we put our faith in God (read: country) and practice His (read: America’s) laws. “A noble task,” as Rameses II would say.

DeMille’s magnum opus would re-create that ideal, orderly, God-fearing society he once knew, despite the magnitude of the changes already taking place within that society. He would also provide the narration for his epic film, thus keeping up a running commentary on the action in a combination Christian-Greek chorus. “And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light,” was DeMille’s opening salvo. His obvious love for his subject, as well as his professed Protestant fervor — not to mention his rabid anti-Communism — were on full display in the seriousness and care with which he vested his pet project, a view that many involved in its presentation equally shared.

Clash of Acting Styles

In spite of the reverence and religiosity present throughout, the finished product laid claim to a wonderful clash of divergent acting styles.

To start, Charlton Heston played Moses as a tough and tender, sincere and long-suffering heroic type. Heston was no method actor, but steeped in the previous generation’s tradition of upright movie role models: John Wayne, Gary Cooper, James Stewart, Randolph Scott, and Henry Fonda — men who were unafraid to foist their beliefs on others, while at the same time upholding the rigid standards set for them by the dictates of the studio system.

Heston brought to his part the same attention to detail and meticulous preparation DeMille had lavished on the whole widescreen venture. That he succeeded in conveying the prophet’s sincerity, given the most stilted of dialogue imaginable, is a testament to his professionalism and humility in the face of such a long and challenging assignment.

For example, he committed whole sections of the Bible to memory, and would often wander off alone into the desert, ruminating to himself on the deeper meaning of the man behind the beard. He would repeat take after take until both he and DeMille were satisfied with the results. The actor has even acknowledged the importance this part played in his subsequent movie career; and certainly, most moviegoers remember him principally for his Moses and his star turn in Ben-Hur (1959), another big-screen religious period piece.

Heston, Brynner & Hardwicke (Paramount Pictures)

In opposition to this was the oriental-looking Yul Brynner, as Rameses II, the arrogant, jealous, vindictive, and abundantly charming main villain of the piece. The Russian-born Brynner — whose real name may have been Tadjie Khan — led a nomadic early life, as the publicity stories spun about him hinted. He was a circus aerialist who sustained life-threatening injuries from a freak fall, a guitar-strumming minstrel, a silver tongued orator and poet, a gypsy, a linguist, a singer, and a gifted stage actor.

But whatever Brynner was, he certainly wasn’t American. He was a “stranger” in a strange land, and, therefore, alien (or “evil”) in the fifties worldview — the perfect foil for Heston’s pure Americanness. Likewise, Brynner’s flamboyant personality was tailor-made for the part, though one half-expected him to insert a few lines of “et cetera, et cetera, and so forth” into the movie’s three-hour-and-thirty-nine-minute running time. The closest the screenplay came to this eccentricity is to have him, and several other cast members, repeat ad nauseam, “So let it be written, so let it be done.”

Taking the phrase to its ultimate conclusion, the film closes with a striking shot of the stone tablets, lighted in a perfect Hallmark greeting-card moment, bearing the inscription: “So it was written, so it was done.”

The traditional Hollywood postscript would prove too mundane for DeMille’s lofty purpose.

The Baldness Factor

Another factor that fueled the Brynner mystique was his obvious baldness. He began to shave his head around 1950, for the role that would be most closely associated with him throughout his life: that of King Mongkut in the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical The King and I. Interestingly, both Eisenhower and Khrushchev were bald, as was DeMille. It is fascinating to note that the U.S. has had only two bald leaders in the past sixty years, “Ike” and Gerald Ford — and Ford wasn’t even a freely-elected president at that. But totally bald principal actors? They were certainly not the norm.

Although many of Hollywood’s best-known male stars (including Wayne, Stewart, Humphrey Bogart, Ray Milland, Edward G. Robinson, and others) wore professionally constructed hairpieces, for a major film actor to assume his “natural” state on the screen, in 1956, was a bold and terribly independent move. This fifties aspect of grandfatherly respectability was not at all present among any of the macho icons of the period. That Brynner had the “head” for it, and became a bankable box-office draw for years to come, was a tribute to his intelligence and durability, in addition to his own innate marketing skills. He knew a good thing when he saw (and shaved) it.

In that same year, Brynner starred in three different productions: DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, the aforementioned King and I, and the screen adaptation of Marcelle Maurette’s play, Anastasia. Each showcased him as a completely shaven lead. He rarely thereafter sported a full mop of hair, even in such Western dramas as The Magnificent Seven (1960) and Westworld (1973). No doubt his sexy, clean-cut appearance helped contribute to his popular appeal, especially among the ladies.

And, should moviegoers not grasp the obvious implication, Brynner, as the absolute ruler of his land, may be viewed as a stand-in for the cue-balled Soviet leader Khrushchev, a rather dubious casting coup on DeMille’s part. The much hairier Heston, on the other hand, remained so throughout the bulk of his movie life, wearing a variety of mustaches, beards, side whiskers, and wigs in many of his most famous parts.

When you consider the latest resurgence of baldness on the large and small screens, via the likes of Vin Diesel (The Fast and the Furious, XXX), Patrick Stewart (the X-Men series, Star Trek: Nemesis), Bruce Willis (12 Monkeys, Unbreakable), Michael Chiklis (The Shield, The Fantastic Four), and James McAvoy (X-Men: First Class, Split), there’s still a good deal of audience fascination with male actors whose sparse pates make up a large portion of their personae.

Looks are Deceiving

DeMille always maintained, and Heston often corroborated, that the decision to cast the then-untested performer in the longest and most expensive motion-picture production in Paramount history was based on the rugged star’s uncanny resemblance to Michelangelo’s statue of Moses in the Roman Church of Saint Peter in Chains. In their respective autobiographies, both director and actor cite not only the astonishing physical appearance, but also the mystical look on Moses’ face, when compared to Heston’s own handsomely chiseled features.

Ever the stickler for detail, DeMille undertook a personal inspection of the statue to verify reports that it resembled his male star — right down to the broken cartilage in his nose. He even had an artist hand paint the actor in flowing robes and wispy white beard to document his confirmation of Heston as the right choice. At least, that’s what the publicity department led moviegoers to believe.

Recent research has revealed, however, that DeMille had another actor in mind for the grueling part: former Hopalong Cassidy and prematurely silver-haired cowpoke William Boyd, an early silent-screen stalwart and DeMille protege. The director-producer had to be “persuaded” to cast Heston as the lead in his mammoth epic.

Almost a decade later, Heston went on to film The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), the story of Michelangelo’s struggle with Pope Julius II (Rex Harrison) to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome — a perfect example of life imitating art, and art imitating life.

Men and Politics

It has often been suggested that Heston’s political education may have been formulated by his constant contact with the conservative-minded DeMille. Heston had already been exposed to him when he was personally handpicked to appear in The Greatest Show on Earth, only his second film feature. The director’s right-wing viewpoints may have possibly swayed the young actor into becoming a veritable poster boy for the National Rifle Association in his later years, or so it was believed.

Certainly, Heston’s participation in a number of family-oriented specials, his recordings of portions of the King James Bible, and the various videos produced with him in the Holy Land — in addition to his penchant for playing religious and historical personages — have fueled the controversy of whether or not his political outlook was shaped by the wily director/father figure.

For his part, Heston claimed not to have spent much time around DeMille. What would the director have thought of his star’s eager participation as a 1960s Civil Rights activist? Or his stint as president of the Screen Actors Guild, or his involvement with the National Endowment for the Arts? The argument does not hold up under scrutiny.

Edward G. Robinson as Dathan

Unlike the American-born Heston, Edward G. Robinson (né Emmanuel Goldenberg) was a Jewish refugee from the East European country of Romania. In the film, Robinson plays Dathan, the chief Hebrew overseer and a traitor to his people. Ironically, HUAC had accused Robinson of being a Communist, even though some of his wartime activities included propaganda broadcasts for the Voice of America program.

At the time, however, his casting was perceived as a risky undertaking, in view of the turbulent political climate. Considering his ethnic origin, it was most disconcerting to see the quintessential movie tough guy playing a tattle-telling, finger-pointing Jewish overseer. Nevertheless, DeMille overcame the negative reaction, and his own loathing for anything remotely Red-tinged, by taking a chance on the dependable stage and screen star.

Miraculously, the role was credited with revitalizing Robinson’s stagnant acting career. He even spouted some colorful (if odd-sounding) repartee with the other cast members at key moments in the story, which added immeasurably to the liveliness of the goings-on. Still, it’s hard to shake off the persistent feeling that Robinson’s acceptance of this role was part-and-parcel to his coming to terms with previous accusations of his having been a Red rabble-rouser, despite being cleared of all charges.

It’s Raining Men

With his fey voice and seemingly mild temperament, the future king of horror flicks, Vincent Price, embodied the lascivious Baka the Master Builder. In reality, Price was an avid art collector, painter, and prolific writer on the subject. He went on to star in many of director Roger Corman’s film adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories, and was highly influential in the work of Tim Burton, who gave the actor one of his best late-career screen roles ever as the creator of Edward Scissorhands (1990).

John Derek played the beefy stone cutter Joshua. Derek was just another hunk on the Hollywood backlot, before gaining a semblance of notoriety as a latter-day Svengali of sorts, by guiding — some would say misguiding — the respective acting careers of Ursula Andress (Dr. No), Dynasty co-star Linda Evans, and the lovely Bo Derek (10).

Veteran character actor John Carradine (the one with the cavernous voice, and father to Keith and David Carradine), is Aaron, Moses’ Hebrew brother; perennial shyster lawyer Douglass Dumbrille played Jannes the High Priest; associate producer and frequent DeMille collaborator, Henry Wilcoxon, is Pentaur, Commander of the Egyptian Host; and British stage and screen veteran, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, portrays Rameses’ father, Sethi.

Also in the large cast were several members who were to gain prominence in the film and television industries, among them former football star Woody Strode (Spartacus, Sergeant Rutledge, Once Upon a Time in the West), Clint Walker (Cheyenne, The Dirty Dozen), Michael Ansara (married to I Dream of Jeannie’s Barbara Eden), and future Mannix star Mike “Touch” Connors. Heston’s infant son, Fraser, plays baby Moses, and H.B. Warner, DeMille’s Jesus in the original The King of Kings, makes a sentimental (albeit emaciated) appearance as Amminadab.

There are guest shots galore by a veritable laundry list of Hollywood has-beens, also-rans, wannabes, and would-never-becomes, including Carl “Alfalfa” Switzer, Henry Brandon (Barnaby in March of the Wooden Soldiers, Chief Scar in The Searchers), Kenneth MacDonald, Luis Alberni, Ian Keith, Onslow Stevens, future Man from U.N.C.L.E. Robert Vaughn, Donald Curtis, Lawrence Dobkin, Eduard Franz, John Miljan, trumpeter Herb Alpert as a drummer (!), and Walter Woolf King (A Night at the Opera) as the Herald. Frank Wilcox, Frank De Kova (Wild Eagle on TV’s F Troop), Francis J. McDonald, and Frankie Darro round out the male contingent of supporting players — and share first names.

Main Squeezes

On the distaff side, Anne Baxter is the temperamental Nefretiri, the beautiful Princess of Egypt, and what a sight she is to behold! She’s a woman who’ll stop at nothing to get her man, and is not the least bit intimidated by the conceited Prince Rameses. She even commits murder for her beau, which makes Nefretiri out to be a character straight out of the film noir school of sexually liberated, headstrong, and possessive female types, obsessed with wielding their sexual power over their men, while using it to achieve whatever devious goals they have in mind (“Moses, you stubborn, splendid, adorable fool!”).

In this, she shares a close kinship to such screen sirens as Joan Crawford (Humoresque, Mildred Pierce), Bette Davis (The Little Foxes, The Letter), Barbara Stanwyck (Double Indemnity), Gene Tierney (Laura), and Lana Turner (The Postman Always Rings Twice) — all of them strong, forthright, and uncompromising females worthy of the name femme fatale.

By contrast, Moses’ Bedouin wife Sephora, languidly played by Yvonne De Carlo, is simple, plain, dull, obedient, and most definitely not your party animal. Not surprisingly, both Baxter and De Carlo were the antithesis of their respective screen roles.

Anne Baxter as Nefretiri

Baxter was American born, and could be coy, charming, shy or minxish in her parts. She appeared as Tim Holt’s girlfriend in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), won a supporting actress Oscar as the dipsomaniac in The Razor’s Edge (1946), and went on to do wonderful work as the backstabbing Eve Harrington in All About Eve (1950), in addition to starring in Applause, the belated Broadway version of the film.

De Carlo was Canadian by birth, and physically much less the demure type. She was a dancer at an early age and appeared in a number of Arabian Nights capers throughout the forties and fifties, before working with DeMille. Later in her career she co-starred as Lily, in the mid-sixties TV series The Munsters. In the show, De Carlo was the epitome of homey, drab domesticity, albeit in green makeup.

Following in De Carlo’s footsteps was Debra Paget, in the part of Lilia, the water carrier. She made several film forays for Twentieth Century-Fox, most notably in Broken Arrow (1950) with Jimmy Stewart, and Love Me Tender (1956) with Elvis Presley, his feature film debut. Paget had her share of flowery costume programmers, including a major role in 1954’s Demetrius and the Gladiators, before fading from view after the early sixties.

The talented Dutch-born actress Nina Foch played Moses’ surrogate mother Bithia. Foch did mostly supporting work early in her career, but gradually expanded into more prominent parts (An American in Paris, 1951; Scaramouche, 1952) before earning an Academy Award nomination as best supporting actress for her turn in Executive Suite (1954).

Martha Scott is Yochabel, Moses’ natural mother. Scott was only nine years older than Heston, but was destined to play his mom again in the 1959 version of Ben-Hur. Olive Deering, who had the small role of Miriam in Samson and Delilah, plays Moses’ sister (also called Miriam). The Australian-born Dame Judith Anderson is Memnet, the minor manipulator of the drama, and Julia Faye is Elisheba. Faye was featured in many of DeMille’s silent epics and early talkies, and was once rumored to have been his mistress. She can be spotted in the Passover Sequence.

Sleeping with the Enemy

The prophet’s early life is all but unknown to most historians and scholars. This did not prevent DeMille from having his screenwriters invent one for him, much as they had done for the mighty Samson. One of these inventions involved an apparently far-fetched (but perfectly acceptable) love affair between him and Nefretiri, the future wife of Pharaoh. The other, although never outwardly mentioned, hinted at the possibility of an interracial relationship with Ethiopia’s Princess Tharbis.

Early on in the film, Moses is seen as a conqueror, but a just and honorable one. He returns home victorious from his siege against Ethiopia, with its King (Woody Strode) and sister Tharbis (Esther Brown) in tow — not as vanquished foes but as loyal allies. Later, Strode re-emerges as one of Bithia’s slave retainers, a poor reward for his allegiance. Tharbis has but one scene, and is the only one of the two with any dialogue. Her words to Moses are, “For he is kind as well as wise.” She presents him with a valuable jewel from her homeland, all the while exchanging knowing glances at him. Their looks are picked up by Nefretiri, who voices a half-concealed, half-jealous aside to Sethi.

It was unthinkable to audiences at the time to even speculate that Moses would have had a sexual tryst with this gorgeous African-American captive. Yet it is not above historical fact — and a guilty pleasure for anyone with an overactive imagination to envision such a prospect. Their dalliance would have made a novel and more believable subplot, with corresponding parallels to Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida (more on that subject below), than the ludicrous Moses-Nefretiri-Rameses love triangle foisted upon the viewer. The subject went curiously unexplored in the film.

What is dwelt upon at length is the subjugation of the Hebrew slaves by the all-powerful Egyptian Empire, indisputably the essential conflict in the drama. It is significant for the time to stress this theme, considering that in Montgomery, Alabama, the boycott against the city’s segregated bus system was gaining momentum from Rosa Parks’ brave act of defiance only a year or so prior.

Civil Rights for Southern blacks were slowly coming to the forefront of national concern, and making steady headway, as the movie came to theaters. For his film project, DeMille chose to focus instead on Moses’ inner struggle and public turmoil over being both Egyptian and Jew, both master and slave, and the inevitable de facto Deliverer of his people. After the unprecedented success of the Montgomery bus boycott brought him to national attention, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. went on to become the modern Deliverer of his people.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The real unspoken issue of the picture, then, is racism, which echoes the true feelings the Egyptian rulers had toward their Hebrew workers. And racism was at the very heart of the disturbances in the segregated South during the mid-1950s, which led to the overdue signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — a modern handing down of the Commandments, of sorts.

Sexual Advances

The fifties was a time of simultaneous sexual repression and re-awakening, as witnessed by the publication of the Kinsey Reports (in 1948 and 1953, respectively) and their “shocking” survey of human sexuality among middle-class white America.

In the movie, many of the characters practice a rudimentary form of sexual promiscuity, as they go from person to person and back again. This cycle prefigures the “Swinging Sixties” lifestyle, what with the spirit of free love and wife-swapping espoused in Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice (1969); and the liberated seventies, with its pattern of aggressive male behavior to be found in such works as Carnal Knowledge (1971) and Shampoo (1975).

Indeed, there was a cloyingly fake wholesomeness to many of the TV programs of the period, most notably in the shows I Love Lucy, Father Knows Best, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, The Donna Reed Show, and Bonanza. They were television’s foursquare way of combating the very real — and more true to the times — feelings of alienation and angst, despondency and despair, loneliness and rebellion found among the nation’s youth, widely felt in such classic screen depictions as The Wild One (1954), East of Eden, Rebel Without A Cause, Marty, and The Blackboard Jungle (all from 1955).

In the example of Lilia, the film’s youthful figure of charm, innocence, and naivete, she is both beautiful and desirable, but in a completely anti-Eisenhower Era way. Except for Joshua, the men in her life seldom see beyond her beauty, merely regarding her for the sexual pleasure they can derive from her. Both Baka and Dathan are in the enviable position to have any woman, but they choose her, a lowly Hebrew slave, instead. Undoubtedly, one of the downsides to hauling water is to fend off your master’s thirst for unsafe sex. Through her own free will, Lilia stays with Dathan (after Moses has disposed of the pesky Baka) in order to protect her true love, Joshua, from certain death in the copper mines of Sinai.

In keeping to the same basic plot device, Nefretiri loves Prince Moses, but loses him to the desert. She then marries the despised Prince Rameses, bears him a son, and eventually throws herself at the born-again Moses’ feet upon his return to Pharaoh’s court. But the now divinely-inspired prophet rejects her persistent — and hopelessly embarrassing — sexual advances.

Nefretiri (Baxter) spurns Prince Rameses (Brynner)

True to his own character’s debauched nature, Prince Rameses in turn demonstrates an absolute disdain for Nefretiri, while displaying a cavalier disregard for her feelings concerning sex. At one point, he brags to her that she will be treated no differently than his other prized possessions, only he will love her more and trust her less.

Moses, too, is not above making a sexual choice of his own. Midway through the story, he is given the diverting task of selecting as wife one of the seven daughters of Jethro, the Sheik of Midian. He at first chooses none, even after they dance so enticingly for him. Subsequently, he sets his sights on the oldest daughter, Sephora, a real “looker,” in 1950s parlance.

Historically, he could have had them all. Since Jethro seems to be a most accommodating sort, he would not have objected to his future son-in-law’s bedding down of all seven of his female progeny. Multiple wives were fairly common among men of means in the Bedouin culture (cf. Sheik Ilderim from Ben-Hur). Naturally, a certain sense of gratitude would have been uppermost in Jethro’s mind for the profitable job Moses had done with his flock of sheep. His daughters appear willing enough. They all-but throw themselves at Moses’ feet in a vain attempt to pique his interest in them.

Music Soothes the Savage Director

As previously noted, DeMille’s picture bears striking similarities to Italian composer Verdi’s 1871 opera Aida, which was originally conceived to commemorate the opening of the Suez Canal. Many of the film’s main characters have close corollaries to individuals in the opera: the jealous Nefretiri can be viewed as a possible Amneris type; the King of Ethiopia is a stand-in for Amonasro, Aida’s father; Moses is Radames, the victorious Egyptian general and Aida’s secret lover; Sethi (or Rameses) is, of course, the King of Egypt; Jannes, the High Priest, is Ramfis, the High Priest; Sephora (or Ethiopia’s sister, Tharbis) is a composite of the title character; and so on.

Truth be told, the association is entirely unintentional. Yet anyone familiar with the opera will detect many such coincidences in the plot of both works: the locale, the costumes, the jealous princess, the war between Egypt and Ethiopia, the political back-stabbing among members of the royal court, Moses and Radames’ dual allegiance, the betrayal for love, the judgment scene, etc., all of which lend further credence to this view.

The melodramatic situations in the movie, in addition to the flavorful, theatrical acting style provided by Baxter, Brynner, Price, Robinson & Company, can be euphemistically described as “operatic”, while the two dance sequences in the film form an interesting counterpoint to the two ballets performed in Acts I and II of the opera. In addition, much of the staging and, in particular, the placement of the actors vis-à-vis the viewer tends to favor a theatrical positioning, as if DeMille were shooting a live play.

But the main element supporting the operatic argument is the complex orchestral score created by novice movie composer Elmer Bernstein. He was known as the “West Coast” Bernstein (as opposed to Leonard Bernstein, the “East Coast” variety).

Film composer Elmer Bernstein

At the time, the favored musical idiom for many mid-fifties productions was jazz and pop, as evidenced by the scores of Leonard Rosenman for East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause (both 1955), Elmer Bernstein’s The Man With the Golden Arm (1955), Alex North’s Unchained (1955), Dimitri Tiomkin’s Friendly Persuasion (1956), and Victor Young’s Around the World in Eighty Days (1956). Several hit songs emerged from these and other features, thus adding to the studios’ box-office grosses and setting a precedent for the simultaneous release of movies with their accompanying soundtracks.

For his film, DeMille insisted on the use of a traditional symphonic score straight out of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Closely following the director’s advice, Bernstein based much of his material for The Ten Commandments on themes associated with the characters and events in the drama, a process not unlike that favored by German composer Richard Wagner, or, as DeMille suggested, what Giacomo Puccini had done with Japanese and American themes in his setting of Madama Butterfly, a work derived from one of Belasco’s stage plays.

It was fate that pointed to Bernstein as composer of choice for this gargantuan assignment. DeMille’s longtime film-scorer of the time, Victor Young, passed away suddenly after completing exhausting work for producer Mike Todd’s elaborate adaptation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. Suitably referred to, and hired by, director DeMille, Bernstein set about writing a most powerful and moving composition for a relative newcomer. It remains a favorite of movie-soundtrack collectors, having been reissued dozens of times on the Dot, Paramount, and United Artists labels.

Building Boom and Urban Flight

There is an enormous amount of building, hauling, lugging, moving, pulling, and tugging all through the picture, as there were in all of DeMille’s main set pieces. His cast of thousands (no exaggeration) seems to participate in never-ending toil and drudgery — or, at the least, in some form of mass movement. It was DeMille’s unparalleled ability to handle crowd scenes, among his other gifts, that brought him widespread fame and recognition in the film industry; and this was nowhere more in abundance than in The Ten Commandments, the ultimate crowd-pleasing picture.

This, again, is reflective of American society as a whole, which boasted the start of the federal and interstate highway systems, along with the building of the model community of Levittown, Long Island, in New York State. Incidentally, the historical Rameses II was one of the ancient world’s greatest builders. For the Hebrew slaves, however, it was more of an American-style dream in reverse, which proved to be a never-ending nightmare for all concerned.

Characteristically, DeMille believed in the Protestant work ethic, which is, if one worked hard in this world one would attain material wealth and prosperity in the next as a reward for one’s labors. But no matter how hard the Hebrew slaves worked, Pharaoh consistently thwarted their hopes for liberation. Sethi’s mad obsession with his Treasure City, his initial appointment of Prince Moses to build it, and Rameses’ subsequent undertaking of the huge building project, resulted in more bitterness and grumbling on the slaves’ part over their forced bondage and increased workload.

This reached a peak in Rameses’ order that bricks be made without straw, as punishment for Moses’ demands that the slaves be set free. This meant they had to glean straw from the fields by themselves prior to making their bricks, yet deliver the same tally (!) of bricks. As much as Pharaoh wanted to show the Hebrews who the boss really was behind the bricks, this was not a very intelligent (or even profitable) use of slave labor on his part, as Prince Moses so adroitly pointed out when he gave the slaves one day in seven to rest: “Blood makes poor mortar. The weak make few. The dead make none.”

Sethi’s Treasure City (accpaleo.wordpress.com)

Throughout the post-World War II boom years, America was driven toward an unprecedented building binge. In New York City alone, hundreds of construction projects were simultaneously underway that included new playgrounds, new parkways, new expressways, new public-housing projects, all kinds of bridges, overpasses and tunnels, and two enormously successful World Fairs.

One can only imagine New York’s master builder, Robert Moses (cf.), being told by one of Gotham’s mayors to build the city’s structures without gravel for concrete, or bolts for steel girders, as punishment for some silly infraction or other. New York City would be a far soggier place without them, and not the Mecca for tourism and finance it was fated to become.

Urban flight was another phenomenon represented by the Exodus of the Hebrew slaves from Egypt. During the 1940s and ’50s, the mass migration of blacks from the poverty, racism, misery, and despair of the rural South, to the perceived “greener pastures” of the industrialized North and Northeast, resulted in big-city budget woes and increased urban turmoil in such places as Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C.

Like the wandering Jews of the Middle East, poor city blacks and other racial minorities were faced with increasing challenges to their daily survival in a location and situation completely foreign to them. Their “manna from heaven” would take the unlikely form of bloated state welfare rolls, depressed public housing projects, inadequate health care, menial lowpaying jobs, demeaning labor, and unequal education — all major and worrisome issues that would come to a head in the decades to come.

Love Affair with the Automobile

What we know as the car culture was born in the fabulous fifties. It reached its apex in everyday life at about this same time. In fact, being able to select an individually tailored conveyance from a vast array of makes, models, colors, and types was what drove the American consumer market forward.

Even more than the object of this uniquely American love affair was the notion of being able to possess such a powerful, sleek, and chrome-covered vehicle as your very own pleasure wagon. Such personal freedom of choice, however, did not exist in the ancient time depicted in The Ten Commandments.

Be that as it may, Prince Rameses’ own love for his chariot epitomizes this obsession with the automobile; in his case, and at the very least, it established the chariot as the principal mode of transportation among the highborn Egyptian elite.

Rameses II in his war chariot

In his initial appearances in the film, the future Pharaoh is seen posing in front of his war wagon, much as any red-blooded American teenager would have done before his ’57 Chevy. Moses’ own entry into the picture is also on board his chariot, as he leads his triumphal procession right under Nefretiri’s window.

With all the work being done on the federal and interstate highways throughout the postwar boom era, America’s factories needed to change over from a strictly wartime footing to a manufacturing one, in order to satisfy the insatiable appetites of car-hungry consumers. These newly minted automobiles were now ready to run on those very same highways, born of necessity, and, let’s face it, rampant and unchecked consumerism.

More than anything else, Egypt’s ceaseless building mania and thirst for dominance were buoyed by Pharaoh’s own vanity and pride in his so-called accomplishments. His massive mobile army units, maneuvered by way of those same chariots, were poised to attack the fleeing Hebrews by the very same means.

For Pharaoh, chariots represented a convenient way to combat those forces opposed to his autocratic rule. They became, for the arrogant Egyptian Empire, its ultimate weapon of mass destruction. As Rameses so sagely put it: “Slaves draw stone and brick. My horses draw the next Pharaoh.”

So let it be done.

Science vs. Religion

The popularity of the scientific method as a panacea for all of life’s ills is put to the supreme test in the film’s juxtaposition of radical views between Moses (now prophet) and Rameses (now ruler) regarding the plagues let loose on the once-fertile Egyptian soil.

Pharaoh and Moses, with Jannes the High Priest

Rameses has a rational explanation for every manifestation that appears: the plagues are but scientifically quantifiable phenomena of natural occurrences found elsewhere in the world. “What gods?” Pharaoh asks. “You prophets and priests made the gods that you may prey upon the fears of men.”

In contrast, Moses champions a more metaphysical outlook to those same phenomena, ergo faith produces miracles. His own transformation from man to mystic, for starters, is an act of religious faith. And if God says there shall be plagues upon the land of Egypt, so let there be plagues.

In DreamWorks Studio’s animated version of the story, The Prince of Egypt, from 1998, Moses’ sister Miriam and his wife, Tzipporah, have a musical number in which they chant in unison, “There can be miracles when you believe.” This song added a Mariah Carey-Whitney Houston diva-esque sensibility to the mix, while at the same time displacing scientific analysis for feel-good gospel vibes.

According to Scripture, Pharaoh was moved by Moses’ pleas to free his people and finally let them depart from Egypt. But the Lord hardened his heart in order that Pharaoh might know that God was God, and serve as witness to the His coming miracles. In the movie, Nefretiri is shown as the main catalyst in this hardening process. After her firstborn son dies from the last of those nasty plagues, she decides to blame not Moses but Rameses (!) for his weakness in allowing the Hebrews safe passage across the sea, thus forcing him to wreak vengeance on the slaves by cutting them off at the pass.

Once more, the humanizing impetus and psychological motivation for this act — however wrongheaded it may have seemed — can only be justified from the scenarists’ point of view. The original biblical narrative is much more dramatic, and gripping, than the flimsy movie excuse provided for us here.

The Rise of Televangelism

As stated in the film’s opening credits, DeMille firmly believed that those who saw his picture would one day be moved to make a pilgrimage over the same hallowed ground that Moses once walked. He understood the unique power of the film medium to move viewers to action. He also had great respect for his audience’s feelings regarding religious representations on the screen.

This view coincided with the revival of Evangelical Christianity in North America and the rise of religious programming on network television. There were regularly televised homilies by the likes of Episcopal Minister Norman Vincent Peale, famous for his self-help book The Power of Positive Thinking, and Roman Catholic Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, with his program Life Is Worth Living, seen by millions across the land.

And then, there was the Reverend Dr. Billy Graham, who broadcast his first televised Evangelical crusades during this same period, as did another golden-throated orator, the Protestant minister Oral Roberts.

Reverend Billy Graham

Both Graham and Roberts began their careers as itinerant missionaries in the late forties and early fifties. They hit upon a winning formula of faith balanced with a passionate, born-again Christian following. Graham’s own Hour of Decision program started on radio, then moved on to television between the years 1951 and 1954.

Billy Graham (a dead-ringer for Charlton Heston in his youth) continued to televise highlights of his popular crusades for years thereafter, earning considerable favor with viewers with each subsequent showing. Certainly, he and his revivalist contemporaries intuitively sensed they could use the medium of television to further the spreading of God’s word to the needy masses of believers waiting to be saved.

TV audiences could be freed of their guilt, their sins, their troubles — and, yes, their hard-earned cash — by tuning in each week for their steady dosage of ready-made religion, just as they would for any pay-per-view, on-demand comedy, drama, action-adventure series, musical variety show, or sporting event.

Religion on the Big Screen

The televangelists in their television pulpits were only emulating on the small screen what moviegoers had been witnessing on the big one. In fact, a regular display of religious pageants — some good, some bad — began their decade-long dominance with DeMille’s own 1949 Technicolor spectacular Samson and Delilah, starring Victor Mature (a star on the rise), Hedy Lamarr (a star on the wane), George Sanders, and the young Angela Lansbury. One could say, then, that the director got the heavenly ball rolling with this over-baked spiritual barnstormer.

This was followed, in 1951, by MGM’s sound remake of Quo Vadis?, which boasted a cast of Robert Taylor, Deborah Kerr, Finlay Currie, and Peter Ustinov as a mincing Emperor Nero; and by Twentieth Century–Fox’s more sedate biblical offering, David and Bathsheba, with Gregory Peck as King David, Susan Hayward as the seductive Bathsheba, and Raymond Massey as the prophet Nathan, with Kieron Moore and Jayne Meadows in fine support.

The success of these films, along with the vast inroads made by television in luring away large numbers of movie audiences, forced the Fox Studios to prepare the next entry in the religious race: The Robe in 1953, starring Richard Burton, Jean Simmons, Michael Rennie, and Victor Mature as the slave Demetrius. This story of Christ’s mantle earned considerable exposure as the first motion picture released in the new widescreen CinemaScope process. It was a huge hit for Fox, which bolstered the release six months later of a sequel, the superior Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), with Mature again, and co-starring Susan Hayward, Michael Rennie as St. Peter, and William Marshall.

Not to be left out in the lurch, RKO cobbled together a version of George Bernard Shaw’s wordy religious drama Androcles and the Lion (1953), with our old friend Mature, Jean Simmons, and Alan Young as Androcles; Columbia Pictures released Salome (1953), with Rita Hayworth as the titular “dancing queen,” Stewart Granger as her love interest, and Charles Laughton as King Herod, in which the heroine dances to save (!) the life of John the Baptist (banal British actor Alan Badel); while MGM bounced back with The Prodigal (1955), an outdated relic starring Lana Turner, Louis Calhern, and Edmund Purdom, and based on one of Jesus’ parables. All three were critical and box office failures.

Warner Brothers, too, assembled an all-star lineup, headed by George Sanders, Rex Harrison as Saladin, Virginia Mayo, and Laurence Harvey, for King Richard and the Crusaders (1954). Warner’s also introduced movie audiences to the young Paul Newman, via the infamously wooden but uniquely stylized staging of The Silver Chalice (1954), based on the best-selling book by Thomas R. Costain.

Jack Hawkins as Pharaoh in ‘Land of the Pharaohs’

The same studio released Land of the Pharaohs (1955), a more intellectually diverting desert precursor to DeMille’s own Egyptian foray of the following year. Directed by the veteran Howard Hawks, it featured leggy London-born vamp Joan Collins goading Pharaoh Jack Hawkins on to ignoble deeds. It was a valiant but doomed effort, despite a literate screenplay by William Faulkner, Harry Kurnitz, and Harold Jack Bloom.

The routine, assembly-line aspect of these celluloid soap operas eventually led to their downfall, and peaked with two major productions from 1959: MGM’s sound remake of Ben-Hur, a multi-Academy Award winner starring Charlton Heston as Judah and Stephen Boyd as his rival Messala, one of the longest and best of the religious epics; and United Artists’ Solomon and Sheba, originally intended as a prestige picture for Tyrone Power, co-starring sexy Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida opposite the villainous George Sanders.

With Power’s untimely death of a heart attack during mid-production, an uncomfortably bewigged Yul Brynner was entrusted to take over the part of the wise Hebrew monarch. The movie was directed by King Vidor and filmed on location in Spain, but neither the exotic locale nor the lush production values helped much at the gate. It was a passionless effort that paled next to the best of C.B. DeMille.

Toward the end of the decade, there was a precipitous decline in the number and quality of these flicks due to over-saturation of the market, competition from simultaneously released works jostling for audience attention, and stratospheric budget demands. One of these, Twentieth Century-Fox’s deluxe retread of Cleopatra (1963), with Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Rex Harrison, and Roddy McDowall, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, nearly bankrupted the studio.

The handwriting was clearly on the studio wall, and signaled the beginning of the end for the religious epic.

Family Ties and Knots

That was the least of Hollywood’s problems, as the basic family unit was being held up to ridicule at every turn, which may have been one reason for the decline in modern religious pictures.

Like the stoic Queen Mum of Great Britain, Egyptian Pharaoh Sethi patiently tolerates the misbehavior of his dysfunctional family group — possibly to gauge the temperament and fortitude of the future ruler of his domain — as he pits his adopted son, Prince Moses, against the offspring of his body, Prince Rameses, in a constant tug-of-war as to who will win the right for Nefretiri’s hand.

But who is this Nefretiri anyway, to whom is she related, and how did she become the object of the two brothers’ most obsessive pursuit, i.e., the sacred throne of Egypt?

The inherent problem with portraying the Egyptian royal family on the screen involves the ancient practice of marrying close relations to one another in order to keep the royal bloodlines pure. Since they considered themselves to be gods incarnate, Egyptian kings and queens could only mate with other gods — and who better to mate with than your own kin? It was generally accepted that brother would mate with sister, and vice versa.

It is never mentioned outright who Bithia’s true husband is, only that she is a widow and a sister to Sethi; nor do we know who Sethi’s spouse is, either. Therefore, it can be conjectured that they could, at some earlier time, have been betrothed to one another; and that Nefretiri may have been the by-product of their union. That would make Princess Nefretiri a blood relative of, if not half-sister to, the insufferable Prince Rameses — a reasonable enough assumption, given the circumstances outlined above.

This could not possibly have been mentioned at the time of the film’s release, for those kinds of incestuous relationships would not have stood up to the censors of the period, nor to DeMille’s pristine vision of a revivalist, Bible-spouting America. It is, however, the only reasonable explanation for her constant presence and influence at Sethi’s court.

Anne Baxter & Charlton Heston, going at it again

In contrast, the Moses bunch is comprised of more standard, working-class family fare, among them his brother Aaron (John Carradine), his sister Miriam (Olive Deering), his natural mother Yochabel (Martha Scott), his wife Sephora (Yvonne De Carlo), his son Gershom (Tommy Duran), his father-in-law Jethro (Eduard Franz), and his six sisters-in-law.

Still, Sephora and her siblings do not take part in the Passover. They are Bedouin sheepherders, and, ergo, more Gentile than Jew. Their ways are not Moses’ ways, yet they have a mutual understanding of his needs — and tend to get out of his way whenever he’s seen preaching about.

During the Passover Seder, the Hebrews huddle together to keep Death from delivering its fatal blow. With this, the Moses family has extended itself beyond the normally accepted boundaries to include his Egyptian stepmother Bithia (Nina Foch), her Ethiopian slave retainers, and several Hebrew worshipers (i.e., Elisheba, Hur Ben Caleb, Mered, and Eleazar among them), who share the prophet’s vision for a better tomorrow.

Upon discovering his Jewish heritage, and after having lived and suffered with his people to learn the true nature of his ethnicity, Moses is banished to the desert for having killed the bullying Baka (Vincent Price), the Egyptian mentioned in the Old Testament account, who whipped poor Joshua into bloody submission after disrupting his liaison with Lilia. “I once killed so that he might live,” claims Moses.

The closely intertwined lives of these various characters, as established by the film’s imaginative screenwriters, are what kept this extended Moses family together through the many trials and tribulations placed in their path. This is strongly contrasted with the visible disintegration of the royal family, commencing with Sethi’s drawn-out death scene, the deterioration of Rameses’ marriage of convenience to Nefretiri, her grasping at an unattainable “lost love” for prophet Moses, and the final demise of her only son and future heir to the throne.

Old Age Slowly Creeping

The passage of time is what, for most viewers, remains the film’s most irreconcilable defect. While Moses and the other Hebrews age noticeably from scene to scene, particularly after the prophet has seen his God, neither Rameses nor Nefretiri, nor any of the other Egyptians at court, age at all; nor, for that matter, do Dathan and his brother Abiram (Frank De Kova) — they are more Egyptian than Hebrew anyway. And as far as ancient Egyptians go, one could say they were already “mummified” before they even died.

But the film doesn’t even live by its own rules, in that it only allows Moses to physically age through the unconvincing growth of longer (and whiter) facial hair and beard. There are no chicken necks, no crow’s feet, no crinkly skin visible anywhere, to give solid evidence to the aging process.

Moses & the Tablets of the Ten Commandments

The prophet is as lean in senility as he was in his youth — and just as talkative, too, which is inconsistent with the biblical narrative that ascribes a stammer and slowness to his speech. His mental and physical acuity, however, remain unchanged: “His eye was not dim, nor his natural force abated.”

Life expectancy at birth in the 1950s was shown to be around 68 years of age for males, and slightly higher for females. Due to advances in preventive medicine and better quality health care overall, as well as free mandatory vaccinations for all Americans, life expectancy rates since the fifties have risen dramatically over the past 60 or more years to its present level of approximately 76 years of age for men (on average), and 81 years for women.

There are no reliable statistics available from biblical times to substantiate any of the claims in it of male or female longevity. Not until the last scene of the film do we even realize that Moses is to be put out to pasture — probably due to his possessing the longest and whitest beard of any of the other male protagonists. This dichotomy in the script has never been satisfactorily explained, but merely points up the picture’s old-fashioned quaintness in preserving for posterity the ideals of beauty, slimness, and desirability among its staple of fifties movie icons, permanently enshrined on celluloid as the glorious screen figures they were intended to be.

The mummification theory set forth above, then, is apparently not as farfetched as it may have seemed.

When the Cat’s Away …

After the plagues of Egypt have done their darnedest, and the parting of the Red Sea has saved the Hebrews from total annihilation by the Egyptians, the actual handing down of the Commandments is pretty much a fait accompli or, more precisely, an anti-climax.

It is here, however, that producer-director DeMille happily comes into his own. He lets his cast of thousands loose on the set to cavort in all sorts of tempting ways, all to convince the greedy spectator of the mass degradation of the wayward Hebrews during Moses’ prolonged absence.

The scene is marvelously choreographed in a raunchy, Bacchanalian-style blitz of activity, with a bevy of beautiful chorus girls basking in the glowing spotlight, amid a bold profusion of gaudy (and eye-popping) Technicolor decor emerging from every frame: from purple, pink, lavender, and rose, to shimmering shades of red, yellow, and blue. Too, there is plenty of dancing and writhing to go around in orgiastic abandon about the Golden Calf, the very symbol of pagan decadence and idolatry. “They sank from evil to evil, and were viler than the earth,” DeMille informs us in solemn voiceover.

At the climax, Moses appears on the summit, looking with thunderous scorn at this impressive array of sinners: “It is the sound of song and revelry,” he declares, in the understatement of the year. Upon his descent from the mountaintop, he gives the children of Israel an apocryphal choice of life and good, or death and evil: “Those who do not live by the Law shall die by the Law.”

Ah, but there’s decidedly more fun in following the Golden Calf than in seeking forgiveness from a bunch of stone tablets, which Dathan opportunely hints at: it may have been carved by Old Man Mose himself — a likely proposition to his disloyal band of supporters, and an eerie reminder to audiences everywhere that even mature adults are wont to act like spoiled children when their fun has been interrupted.

God’s laws are basically blueprints for his flock to follow, a how-to guide to a fuller and happier life. In the Christian faith, we know that Moses was a harbinger of Christ’s coming. His tale of suffering and sacrifice predated that of Jesus’ own woes by several hundred years, and their inspiring stories share similar themes and events.

We are also taught that the Old and New Testament prophets were symbolic of what will surely come to pass for us all: that is, our own death and resurrection, which represent the longed-for hope for better things to come — if not in this world, then certainly in the next.

The End in Sight

Parting of the Red Sea (Paramount Pictures)

So, too, was the hope of postwar America in the mid-1950s. God’s awesome power, as He parts the mighty waters for the Hebrew slaves to safely pass through, becomes, by necessity, a doomsday weapon of its own, to combat Pharaoh’s formidable forces of chariots and spears.

Dark storm-clouds gather and threaten, in the now familiar and unmistakable form of a billowing mushroom cloud (in reverse), that leave us with the final, uneasy image of America’s nuclear arsenal, poised at the ready should any of our meddlesome foes dare to intervene in our worldly affairs — especially in our never-ending pursuit of life, liberty, and happiness: “The Lord of Hosts will do battle for us,” cries Moses to his flock. “Behold, His mighty hands. Who shall withstand the power of God?”

Who indeed?

Freedom has its own permanent and immutable rewards. There can be no better, nor more consistent — nor more fifties — movie message than this. The price for it is eternal vigilance. ◙

Sources & Recommended Reading:

- Eames, John Douglas. The Paramount Story, Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1985.

- Essoe, Gabe and Lee, Raymond. DeMille: The Man and His Pictures, Castle Books, New York, 1970.

- Katz, Ephraim. The Film Encyclopedia, Second Edition, Harper Perennial, division of Harper Collins, New York, 1994.

- Kaledin, Eugenia. Daily Life in the United States, 1940-1959: “The 1950s: The Postwar Years and the Atomic Age,” Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 2000.

- MacDonald, Laurence E. The Invisible Art of Film Music: A Comprehensive History, Ardsley House Publishers, Inc., New York, 1998.

- Munn, Mike. The Stories Behind the Scenes of the Great Film Epics, Illustrated Publications Company Ltd., Argus Books Ltd., Watford, Herts, England, 1982.

- Nadel, Alan. “God’s Law and the Wide Screen: The Ten Commandments as Cold War ‘Epic’,” PMLA, Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, Volume 108, Number 3, pp. 415-430, May 1993.

- Nichols, Peter M. “When DeMille Was More Auteur Than Showman,” The New York Times Publishers, New York, June 22, 1997.

- Orrison, Katherine. Written in Stone: Making Cecil B. DeMille’s Epic, The Ten Commandments, Lanham: Vestal Press, 1998.

- Raymond, Emilie. From My Cold, Dead Hands: Charlton Heston and American Politics, University Press of Kentucky, 2006.

- Rovin, Jeff. The Films of Charlton Heston, Citadel Press, Secaucus, New Jersey, 1977.

- Segal, Alan F. “The Ten Commandments,” Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies, Mark C. Carnes, ed., Henry Holt & Company, an Owl Book, New York, 1995.

- Steinfels, Peter. “Looking Away From DeMille to Find Moses,” The New York Times Publishers, New York, April 7, 1996.

- “The Movie Epic,” The Perfect Vision Magazine, Volume 6, Issue Number 22, July 1994.

Copyright © 2012 by Josmar F. Lopes (revised July 2016) All rights reserved

You must be logged in to post a comment.