Sophia Loren (Aida) & Afro Poli (Amonasro) in the film version of Verdi’s Aida (1953)

Lights! Camera! Opera!

From Puccini to his illustrious predecessor, Verdi, came my first full-fledged exposure to the Bear of Busseto’s grandest of grand operas, Aida.

Originally conceived to inaugurate the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal in Egypt, Aida made its debut a few years later (in 1871) at the Cairo Opera House. Besides being one of Master Verdi’s most sonorous stage spectacles, there are moments of unanticipated intimacy and orchestral lightness — for example, the famous double scene of Act IV where Aida and her lover, Radames, are locked in each other’s arms while sealed alive in the tomb.

As many of this blog’s readers know, my first experience with a live radio transmission of a Metropolitan Opera production was the four-act Aida. The cast, as far as I can remember, was headed by the legendary Leontyne Price in her signature role of the Princess Aida, with James McCracken as Egyptian general Radames, and Robert Merrill as Aida’s father, Amonasro. The year must have been around 1967 or ’68 (maybe even earlier).

It also marked the moment I first started recording reel-to-reel tapes of Saturday matinee performances. This practice went on for decades thereafter (with portable cassettes supplanting tapes), but at the start I only recorded arias and highlights, or the most memorable portions of acts and scenes (memorable to ME, that is) instead of the whole darn thing. This was the case with Aida: I got as far as Act II, the noisiest and most lavish of the four, before I ran out of tape.

As was the norm for me back then, Aida quickly became my most listened-to showpiece. It remains a favorite of mine, though slightly down from that imaginary “best of” list. Right now, I would rank it in the top ten. It’s an opera I know well, one I have grown to admire for its well-developed story line (Verdi himself had a major hand in shaping the drama and dialogue) and musical ambition (Act IV, Scene One, also known as the Judgment Scene, stands as one the composer’s finest and most forcefully structured sequences for mezzos).

With all young people, curiosity manages to bring out the best in them. Not only was I not satisfied with just learning the words and melodies to the most popular airs, but I began to realize there were actual stories behind these great works. This led me to the next series of events in my burgeoning operatic life: a subscription to the Met’s weekly magazine, Opera News, published by the Metropolitan Opera Guild.

At that time, a dollar would buy you a month’s worth of material about the radio broadcast, the cast of performers, the goings-on in the opera world and other opera-related matters — a dream come true for initiates. This jump-started me into a nonstop chain of reading and writing about opera from a multiplicity of reference books and library resources, in addition to listening to every opera broadcast I could adjust my radio dial to, along with independent study that, to this day, continues to thrill and delight me as it always has.

I mention independent study as a key component of getting to know what opera was all about — and how my juvenile (at times, practically obsessive) interest in Aida paid off handsomely both on television and in the movie theater.

One summer, my father informed me that a downtown cinema was advertising an old Sophia Loren picture: Verdi’s Aida — billed, as a double-feature, with a matinee showing of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. Off we went to see my first opera movie. Heck, I didn’t know Sophia Loren could sing opera! Neither did she — how naïve was that?

Unbeknownst to moi, Sophia’s singing voice was dubbed by Italian soprano Renata Tebaldi, whose own full figure was, (ahem) shall we say, more “ample” than La Loren’s. As I watched the screen, it quickly dawned on me that none of the other artists appearing in this color production had done their own singing as well.

Lois Maxwell (Amneris), who played Miss Moneypenny in the James Bond series, with Sophia Loren (Aida)

What startled me the most was the overpowering stereophonic sound reproduction and the ampleness of the voices with full orchestral accompaniment. Wow! What a thrill it was to hear opera at full blast! At that point, my only exposure to music of this nature was consigned to a crude portable record player (with constricted monophonic output, at that) and to a 13-inch black-and-white TV set, where shows such as the Bell Telephone Hour broadcast kinescope images of old-time opera stars in their sunset years.

If I wanted to live the life operatic, I had to dispose of those elementary pieces of equipment and graduate to more sophisticated listening methods.

Along those lines, I vowed to expand my classical horizons by kicking things off with the purchase of a complete opera album of Aida. No longer would I be limited by arias and highlights. I wanted — and needed — to hear and learn about the entire work, from beginning to end, top to bottom, no more lame excuses.

Impressed as I was by the voices onscreen, I was a little thrown by the baritone who performed the part of Amonasro. To me, the voice had to belong to the great Tito Gobbi. Surely, that snarling tone and snappy delivery could have come from no other singer. In fact, I had recently heard Gobbi in the opera’s Nile Scene with Maria Callas on music critic George Jellinek’s program, The Vocal Scene, on radio station WQXR-FM.

By way of research, I learned that the actor who embodied Amonasro on film was Afro Poli, a decent enough singer in his own right, but even he had been dubbed by another artist, the late Gino Bechi. Bechi, I came to realize later, turned out to be one of the singers that had inspired the young Gobbi when he was starting out in the opera field.

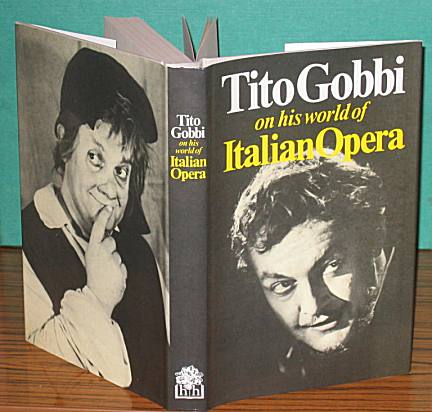

Gobbi wrote about Bechi in his autobiography, My Life, and in his book Tito Gobbi and His World of Italian Opera. Here is what Gobbi had to say about his great colleague and rival: “Gino Bechi and I had a sort of competition between us as to who could sing [Baldassare’s aria from Cilèa’s L’Arlesiana] better, and even to this day I have the stupendous voice of Bechi in my ears.” Gobbi was a most generous soul.

Tito Gobbi and His World of Italian Opera

I knew, too, from prior investigation, that Bechi had sung Amonasro on an old 78-rpm recording, with Gigli as Radames and Maria Caniglia in the title role. Heck, I had about as much chance of finding that album as I would have in purchasing an old-fashioned gramophone to play it. Maybe I could settle for Gobbi’s masterful interpretation with Callas and Richard Tucker, an EMI/Angel release of more recent vintage and (it was my hope) availability. It wasn’t in stereo, mind you, but was the next best thing.

Armed with money my mom gave me, I went down to E.J. Korvette’s, a popular department-store chain at the time, in search of Signor Gobbi. No such luck! However, I did find a complete RCA Victrola recording with Zinka Milanov as Aida, Jussi Bjoerling as Radames, Leonard Warren as Amonasro, Fedora Barbieri as Amneris, and Boris Christoff as the High Priest Ramfis. This was a re-release of the original RCA Victor outing which, if memory serves me, didn’t always carry a libretto — something I desperately needed if I was going to accompany along.

Faced with either this purchase or nothing, I decided to go for it. Returning home, I eagerly played the album from start to finish (with libretto intact) and was not dismayed at the result. This was a splendid production, with excellent acoustics (albeit sonically restricted in one instance towards the end of the Nile Scene) and immaculately refined singing from all the participants. Whoever said that Aida was nothing more than a pretentious excuse for camels and circus elephants was dead wrong!

The recording venue was the Rome Opera House. Consequently, one could feel the surrounding ambience’s sway, which had a positive effect on the individual performances and interpretations. But don’t take my word for it. Read this section from Volume One of Opera on Record, edited by Alan Blyth, published by Hutchinson & Co., and written by contributor John Steane:

“Milanov’s voice has something in common with [Montserrat] Caballé’s, excelling in the soft, high notes which were at best pure velvet. In other, more turbulent passages, she could be less pleasing, losing focus and displaying a beat. Some most lovely singing by her and Jussi Bjoerling in duet, however, should be preserved if ever a really adequate archive comes into existence. ‘La tra foreste vergine’ (Bjoerling also observing that rare dolce marking) and ‘O terra addio’ haunt the memory long afterwards with their loveliness.

Jussi Bjoerling (top left) & Leonard Warren (middle) listening to a playback of Aida

“This set, too, is probably the most striking of all in the way it opens (once the curtain is up): Bjoerling is in his best voice, fullest voice, but the first voice of all that we hear is Boris Christoff’s, so impressive that it bids fair to refocus the whole opera on the High Priest.”

What was that about Gobbi and Amonasro? Live and learn.

A Resounding Ring

My other life-altering discovery came with Sir Georg Solti’s compelling rendition of the first note-complete, stereophonic realization of Wagner’s epic Ring of the Nibelung. This massive cycle is comprised of four evening-length works, starting with the shortest, Das Rheingold (“The Rhine Gold”), and continuing on (in ever-increasing lengths) with Die Walküre (“The Valkyrie”), Siegfried, and the longest of the lot, Götterdämmerung (“Twilight of the Gods”).

Supplied with lavish librettos and copious program notes and background information, I threw myself into Wagner’s mythological setting — the operatic equivalent of a pre-Lord of the Rings saga — with the daring of a Spanish explorer visiting the New World for the first time.

With the additional aid of the Rheingold booklet, which set forth and illustrated the complicated leitmotif (“leading motives”) system that Wagner employed throughout the telling of his story (along with a three-disc album of appropriate musical excerpts annotated by British music critic Deryck Cooke), I was aurally and visually able to follow the complicated plot’s many meanderings with the ease of a specialist. I finally began to understand what motivated the characters to do what they did — and uncovered for myself the raison d’être for Wotan’s deplorable (nay, inexcusable) behavior with respect to his minions. And he’s supposed to be the head god, the one those lesser gods and mortals looked up to? Why, he’s no better than his counterpart, Alberich.

One of the mysteries that was cleared up was why Alberich, the loathsome Nibelung of the saga’s title, is called Schwarz (“Dark”) Alberich, while at other times Wotan is mentioned as Licht or “Light” Alberich. They are, in fact, mirror images of each other, with both good and bad traits abounding. Wotan wanders the world, looking for love away from home and hearth. He fathers various siblings along the way, all of them out of wedlock, while still married to Fricka, his lawful wife. In addition, he condones the incestuous pairing of his children, Siegmund and Sieglinde — an uncomfortable set of circumstances that brings about their downfall.

Similarly, Alberich is searching for an amorous tryst with the voluptuous Rhine Maidens, who spurn him for his ugliness. Thus Alberich renounces love, places a curse on the titular Ring, and pays another woman, Grimhilde (huh, “Grim” is right!), to bear his only son, Hagen, the personification of hatred and evil incarnate. Can you blame him?

With understanding comes an appreciation for what the singers have to do in order to convey these various implications in their respective characters. Does the singer portraying Wotan express power and will when called for, but can he also be wimpy and weak when confronted with Fricka’s arguments? Can the artist assuming Siegfried represent youthful exuberance in forging the sword Nothung, and can he later do justice to the telling of his life story to the Vassals, which comes after a long, eventful night of full-throated warbling?

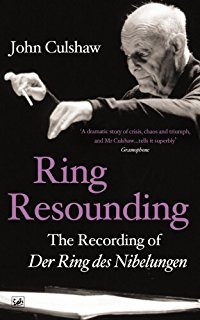

John Culshaw’s ‘Ring Resounding’

These are some of the myriad aspects to look for when listening to a performance of the Ring. It’s one thing to find them in a live performance, but on records? The odds are doubled at every turn you won’t encounter them. But you would never know it if you didn’t read up on the story ahead of time. Plunging head-long into the River Rhine is not everyone’s preferred method of discovery. But in my case, it became a revelatory experience — that, and my reading of Robert Donington’s fascinating tome, Wagner’s Ring and Its Symbols, a rather Jungian interpretation of the events in the drama. I can also recommend (if you’re interested) Father M. Owen Lee’s Turning the Sky Around, a much shorter but equally incisive analysis of the work by way of Father Lee’s intensive study of classical literature.

Interpretation. That’s a much abused word in the world of opera, especially when the conversation turns to Regietheater, or “director driven theater.” Should the director be the driving force behind most of the world’s productions? Or should he or she be constrained by past performance practice? It’s fair to view a work with fresh eyes, but too often directors want to push the outside of the envelope for no other reason than to push it as far as it goes. Is this a valid, reasoned approach or plain old, self-indulgent willfulness?

On records, one need not worry about such contrivances. In this specific environment, “interpretation” is relayed by words and sounds alone. There is no visual component to throw viewers into a quandary. Only the sonic elements suffice, which can either lead to a more positive experience with the recording at hand or a negative one.

Returning to Solti’s Ring, I’d like to answer an age-old question that’s been posed by countless critics and record buffs for well on 60 years, at least since this archetypal edition first appeared on the shelves: was this the best-ever “interpretation” of Wagner’s magnum opus? Hmm, that’s a tough one. Considered a landmark in the history of recorded opera, the first stereophonic Das Rheingold was released back in 1958, followed a few years later by Siegfried in 1962, Götterdämmerung in 1964, and finally Die Walküre in 1965.

Lauded for its sonic splendor and superb sound reproduction and effects, producer John Culshaw earned kudos for his team’s efforts in capturing for all time such iconic performers as Kirsten Flagstad, Hans Hotter, Set Svanholm, Gottlob Frick, Paul Kuen, and Gustav Neidlinger, along with a younger generation of Wagnerians headed by Birgit Nilsson, Wolfgang Windgassen, Regine Crespin, Christa Ludwig, James King, George London and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau.

The enterprise was unique in that entire episodes were recorded in extremely long takes, some sessions by as much as 45 minutes or longer. This was not a common practice at the time. In truth, most opera albums were recorded piecemeal and, in the manner of the majority of motion pictures, totally out of sequence.

So what made this venture so unique? My own view of this issue lay in the casting. In his book on the recording, entitled The Ring Resounding, Culshaw described the difficulties the company had with the artist scheduled to undertake the part of Siegfried, a key role. You will notice that there is a four-year gap between the release of Rheingold and Siegfried (why they did not record the next opera in the series, Die Walküre, remains a mystery).

Georg Solti (left) & producer John Culshaw recording Wagner’s Ring

One of the reasons for the long delay was caused by Ernst Kozub, the unmentioned tenor assigned to sing Siegfried and who had captured everyone’s attention with his stirring voice. Culshaw insisted that Kozub had the raw equipment that would turn him into a star of the first magnitude, if only he had more in-depth study and dug into the text with added insight. But no matter how they tried to coach him, Kozub resisted; worse, he became incapable of delivering the goods needed to bring the character to life. Not known at the time were issues concerning Kozub’s health, which were never revealed until much later.

Reluctantly and with so much time and money invested in the project, Culshaw was forced to look elsewhere for his Siegfried. He was fortunate to secure the services of the leading Wagner tenor of his day, the French-born German singer Wolfgang Windgassen. Without mincing words, it was clear to everyone involved that this was a world-class interpreter. The only problem was securing his services, for which contract negotiations were long and drawn out.

Business was finally settled, mostly due to Windgassen’s personal efforts on the project’s behalf. Culshaw confessed that much dial-twiddling and sound recalibration was called for in overcoming the size differential between Windgassen’s more modest tone and Kozub’s more refulgent one. What Decca/London gave up in impact and immediacy they gained in a decidedly enhanced, artistically viable interpretation (there’s that term again) where the artist in question outshone all previous attempts. Windgassen gave it his all so that both Siegfried and Götterdämmerung could be completed.

To underscore the point Culshaw made above, there are several moments in these two works where Siegfried reveals an innermost depth and nuance not native to his abrasive character. One of them is the delightful Forest Murmurs Scene from Act II, at the spot where the young brute longs for his dead mother, whom he never knew in life. Windgassen is so effective and affecting here, with a real tenderness and awareness for the words and text, that all thought of another singer doing justice to the part is swept aside. His forceful yet exuberant Forging Scene is spot-on terrific, too, aided and abetted by Gerhard Stolze’s cacophonous Mime and those marvelous poundings of the anvil.

In Act III, things turn deadly serious with Siegfried’s dramatic encounter with the Wanderer (Wotan in disguise). Having disposed of this meddlesome pest, Siegfried approaches the fiery rock where Brünnhilde lies asleep, surrounded by Magic Fire (the Sleeping Beauty story taken to the extreme). As Siegfried muses on the figure before him, he cautiously removes her breastplate. Then, in a violent outburst pregnant with comedic potential, he cries out: “This is no man!” But it’s the WAY that Windgassen handles this moment, how he shapes this phrase that betrays not humor but terror at the thought of befriending such an extraordinary creature as this.

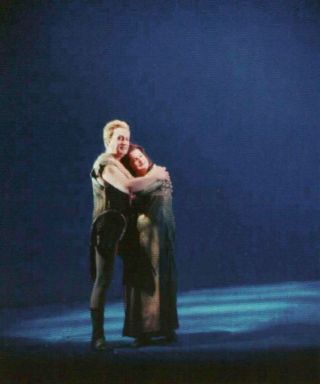

Wolfgang Windgassen (Siegfried) embraces Birgit Nilsson (Brunnhilde) in Siegfried (Photo: Bayreuth)

Finally, with a long, all-enveloping kiss on her mouth, Siegfried awakens Brünnhilde to the simultaneous rising of the dawn. The theme of the rising sun resounds in the massive Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (recorded in Vienna’s acoustically ideal Sofiensaal), as it accompanies Birgit Nilsson’s mighty voice in her bid to welcome the morning light: “Heil, dir, Sonne! Heil dir, Licht!” She takes the phrase in one long, astounding breath.

It’s just one of the many spectacular sequences from this epic undertaking that provide all the proof one needs to confer its premier status as a high-water mark for recorded opera.

Ripe for Re-Disc-covery

The advent and promise of the compact disc, or CD, and the expectations it engendered as a viable “new” medium for preserving opera eventually sealed their fate more that it revived a by-now waning format. Anything and everything worth recording had already been done, or so the prevailing thought. Besides, where were the present-day artists who could replace the likes of a Pavarotti or a Domingo? The newest Caballé or the latest Price? Where was Milnes’ successor, or Ghiaurov’s or Ramey’s, for that matter? You get my drift.

Without an alternative replacement of the magnitude and resilience of the above-named artists, what purpose was there in re-recording something that had already been recorded a dozen or more times before — and better performed at that? Just to hear an opera in another medium, that is, in the digital realm, is that reason enough? How many inferior versions of Tosca or La Bohème can we handle? How many opera albums can pop idols and wannabe opera stars such as Andrea Bocelli or Josh Groban headline, to the inevitable damage of the very product they are attempting to sell?

Maybe I’m letting my inner “grumpy old man” get the better of me. But let’s be honest, here: when has anyone been bowled over by the current batch of complete opera recordings? What I have seen revived of late (and fairly successfully, too) is a welcome return to the single artist set-up — that is to say, the concept album: recitals and concerts of scenes and extracts from well-known or rarely performed operas and songs, recorded and sung to near perfection in a controlled atmosphere.

For an illustration of what I mean, we have Roberto Alagna’s Malèna, Jonas Kaufmann’s An Evening with Puccini, Dmitri Hvorostovsky Sings of War, Peace, Love and Sorrow, Pretty Yende’s A Journey, Anna Prohaska’s Serpent and Fire, Lawrence Brownlee’s Allegro Io Son, Anna Netrebko’s Verismo, Elīna Garanča’s Revive, and Jamie Barton’s All Who Wander. Each of these fine artists, in his or her own way (and in his or her own voice), has contributed to a better understanding of their respective country’s art.

Choice items and representative highlights from their concert programs, be they from North America, Italy, France, Spain, Mexico, Germany, Latvia, Russia, South Africa, or wherever, stress the diversity and depth of music and song in this big old world of ours. To coin a well-worn phrase, they each have offered audiences “something old and something new, something borrowed and something blue.” Something “blue” in this context would refer to something sad, but no matter.

My own feelings about this direction that opera recordings have taken, despite the diffuse nature of today’s constantly evolving technology, is one of joy and hopefulness. Joy that this newest crop of singers and artists, from sopranos to tenors, mezzos to basses, baritones to countertenors, are finally able to penetrate the storm clouds of uncertainty; and hopeful that tomorrow, they will bring forth the light of understanding as to what the operatic art truly involves: dedication, perseverance, suffering for one’s art, and, above all, a love for the form.

(To be continued….)

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes