“I am a HAL 9000 computer” from 2001: A Space Odyssey

Stanley Kubrick’s timeless visionary epic, originally billed (and titled) as a “journey beyond the stars,” is a film that’s solemn and slow moving, stately and portentous to the nth degree, but a bona fide science-fiction classic nonetheless. The elegance, serenity, poetry and majesty and, above all, the mystery of outer space are preserved in all their widescreen, Cinerama-esque splendor.

Released a little over a year before NASA successfully landed two astronauts on the Moon, 2001: A Space Odyssey, while certainly not the first (nor, heaven forbid, the last) FX-laden extravaganza to depict the hazards of space travel, is considered by many followers of the form as the granddaddy of all those intergalactic sleigh rides we’ve grown accustomed to viewing throughout the years, among them the Star Trek and Star Wars series, Alien and its progeny, Outland, The Right Stuff, 2010: The Year We Make Contact, Prometheus, Gravity, Interstellar and our latest candidate for consideration, The Martian.

Now tell me: has any science-fiction feature of the last forty years or so ever been more fully realized on the screen than Kubrick’s acclaimed masterpiece? The work that went into the final product is truly breathtaking in its vastness, scale and dimension.

Filmed mostly on the soundstages of M-G-M British Studios, Ltd., in Boreham Wood, England, with an unprecedented array of special photographic elements and visual effects, the film was personally supervised by Kubrick himself, along with able assistants Wally Veevers, Douglas Trumbull, Con Pederson and Tom Howard — all of them handling such diverse aspects of the production as lighting conditions, camera movement, shutter speed, color, temperature, and so forth, with single-minded dedication and meticulous care for detail. Not surprisingly, the film took three years to complete, at a cost of almost US$12 million — and it shows.

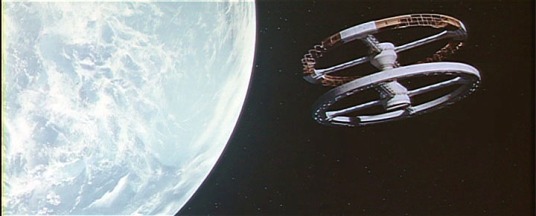

Earth and the Space Station in 2001: A Space Odyssey

The story: highly evolved super-beings deposit their calling card on Earth (and on the Moon), in the form of a large, rectangular-shaped black object known as the monolith. With the object’s extraordinary ability to implant suggestions into their brains, primitive man-apes are taught to use rudimentary weapons (e.g., the jawbone of a wild pig) in order to gain dominance over their foes, as well as their harsh environment. The evolution of these man-apes into Homo sapiens leads to the next phase of their development, with man literally branching out into new worlds — both physically and metaphysically — far beyond his own.

But what does it all mean? The ambiguously written screenplay by producer-writer-director Kubrick and science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, after his short story “The Sentinel” from 1948, and partially based on themes found in Clarke’s 1952 novel, Childhood’s End, explores cosmic questions of the specie’s origins, its ultimate purpose and, inevitably, its fate. The script, much expanded from the original story, takes up the premise that aliens of a higher order — with an advanced intelligence surpassing our capacity for comprehension — are “out there,” watching, waiting and guiding our planet’s destiny from an unseen corner of the universe.

Perhaps the best way to come to grips with Kubrick’s overall approach to this film is to see it in terms that relate to the context of the times in which it was planned and executed. For example, the two pictures that came immediately before and after 2001: A Space Odyssey — i.e., Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and A Clockwork Orange (1971) — may provide the necessary clues toward understanding what the director had in mind for his central project.

In these films, civilization is depicted as being in three distinct stages of development (or disintegration, if you prefer): in Dr. Strangelove, mankind is perilously (albeit farcically) on the brink of nuclear annihilation; in 2001, it has left the Cold War mentality behind and instead appears to be poised for a miraculous rebirth; and in A Clockwork Orange, society is back to teetering on the edge in a fundamental collapse of the social order.

Dr. Strangelove, the first work in Kubrick’s film trilogy, has frequently been described as a satire, a tongue-in-cheek black comedy of the darkest order where man’s best laid plans for avoiding Armageddon are suddenly thwarted by renegade generals with sick minds; while the middle entry, 2001: A Space Odyssey is too often treated with an earnest solemnity bordering mysticism. Make no mistake, Kubrick did have a deadpan sense of humor; and indeed Dr. Strangelove offers viewers some rare relief from his more sedate tendencies. It, too, is a comedic masterpiece of Shakespearean dimensions, with characters that are akin to a Jack Falstaff or the doggedness of Constable Dogberry from Much Ado About Nothing.

The infamous War Room in Dr. Strangelove (1964)

While it does take itself seriously, 2001: A Space Odyssey also offers brief glimpses into the lighter side of life’s little inconveniences. Take, for example, Dr. Heywood Floyd’s attempts to decipher the list of instructions needed to operate the space toilet; or the manner in which the super-computer HAL 9000 reverts to a song from his “childhood” (“A Bicycle Built for Two”) when faced with termination.

By contrast, A Clockwork Orange merges the two forms of black comedy and drama, along with traditional English dance hall routines, into an overridingly pessimistic view of society; one that is both cynical and disorderly — with British society, in this instance, in desperate need of “aversion therapy” (the so-termed “Ludovico technique”) in order to purge selected subjects of their wanton aggression.

This technique forces participants to keep their eyes open as they watch scenes of untold violence, while at the same time listening to Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, “Ludwig” being the German variant of Ludovico, a version of the English and French “Louis.” Why, even names have begun to lose their substance and individuality: to connect this seemingly questionable technique — and, by that connection, British society as a whole — with one of Europe’s greatest anti-war composers is an irony of titanic proportions.

Here, the general misbehavior is caused by the prevalence of street thugs (called droogs) which has given rise to a police state. The droogs have laced their drinks with a powerful stimulant that feeds their predilection for rape and violence. After a particularly perverse night of recklessness, droog leader Alex is captured by the police and sent to prison to be “rehabilitated.” It’s at the prison that many of the wickedly humorous episodes occur, among them a coldly calculated search of Alex’s body cavities by the no-nonsense chief guard Barnes.

The “droogs” from A Clockwork Orange (1971)

The madness of human behavior witnessed and unleashed in Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange and the mania in these films for all-out mayhem and destruction is contrasted with the anodyne expressions of the two human astronauts in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The men appear drained of feelings, the bulk of which have been transferred onto the personality of their HAL 9000 computer with its matter-of-fact vocal inflections and paranoid, single-minded resolve for self-preservation. It’s no accident that HAL is the most human character in the story.

The lack of an emotional response can be measured by the over-abundance of emotions present in Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange. In the earlier flick, the dialogue remains fast and furious throughout; the words pouring forth in a never-ending torrent of verbal hemorrhaging and rapid-fire delivery (most notably in George C. Scott’s over-the-top performance as the bombastic General Buck Turgidson), their meaning coming through loud and clear no matter the pace. In A Clockwork Orange, the droogs speak a type of street language, a combination of Russian tinged with Cockney slang, while the rest of the population converses in standard British English. No matter how they talk, each group gets their point across; soon, even the viewer is able to make sense of the gibberish.

Compare the above scenarios to 2001, where the dialogue has been purged of all meaning and relevance. In fact, not a word is spoken (the film’s opening sequence takes place at the Dawn of Man) until a good half hour or more has transpired. When the human characters do speak, their tone and substance is devoid of clarity and lucidity. We hear the words, but they have no connection to the action at hand, their meaning having been divested of any and all emotional impact.

Dr. Floyd (right) meets with Soviet scientists at the space station

One excellent example comes in Dr. Floyd’s chance meeting with his Soviet counterparts aboard the floating space station. One of the scientists, Dr. Andrei Smyslov, questions him about a possible epidemic at the moon base Clavius where Floyd is scheduled to give a briefing. Their exchange is so elliptical and circuitous that absolutely nothing is learned or divulged about the matter at hand. Even more maddening is the subsequent meeting at the base, where the participants’ conversation is so completely on the surface, so to speak, that precious little is conveyed through words. It’s as if words have lost their meaning.

Another comparison can be made with two similar sequences, both having to do with the futuristic videophone technology. Back at the space station, Dr. Floyd puts in a call to Earth to wish his young daughter a happy birthday. Floyd does most of the talking, as his little girl (played by Kubrick’s daughter Vivian) responds in shy, monosyllabic fashion. Flash forward to the spaceship Discovery, where astronaut Frank Poole is about to receive an incoming video message from his parents back on Earth. They, too, want to wish him many happy returns. Frank listens stoically to their greeting in stone-cold silence, maintaining an impassive air throughout the one-sided conversation. When he does speak, it’s to ask HAL to raise the head of his cot ever-so slightly. The impression Frank gives is of conserving his words and energy for more “important” purposes than a birthday greeting. His “humanity,” if you want to call it that, has been drained from his person in preparation for the trip.

There’s one more incident involving the use of language (or meta-language, in this case) that is certainly the most “revealing” moment in the entire picture. It’s the scene where Frank Poole and Dave Bowman are inside a sound-proof space pod, discussing the problematic issue of HAL’s mistaken prediction of a failed component. Mission Control has reported back to the pair that their super computer’s findings regarding the faulty circuit are in error. When asked his opinion, HAL reiterates the mantra that human error is no doubt to blame for the misdiagnosis.

Frank & Dave are spied upon by the HAL 9000 computer

As the two astronauts continue to engage in a deadly serious conversation about the possibility of pulling the plug on their computer, the camera moves back and forth from Dave’s mouth to Frank’s lips, and so on. There is no sound except the constant low-level hum of super-computer HAL’s circuits. His unblinking, all-seeing red eye (and the audience’s as well) is alert to the astronaut’s thoughts, even though no words are forthcoming. At this point, not only are the sounds of their words unnecessary for comprehension, but their meaning can be gleaned from the context of the situation. HAL has proven, once and for all, that words can be dispensed with amid a super-computer’s need for survival.

In a space-age variant of “rehabilitation,” at the movie’s climax man must give up his humanity in order to be reborn as the Star Child. This is represented in the moving sequence whereby Dave, after rescuing his dead partner Frank from HAL’s treachery, is forced to release his colleague from the pod’s human-like appendages. Slowly and methodically, Dave gives up Frank’s lifeless body to the immensity of space itself, an offering (such as it is) to the heavens. Similarly, HAL must take on man’s humanity so as to maintain some semblance of balance in the universe: from chaos (Greek for “disorder”) to cosmos (or “order”).

The Pod releases astronaut Frank Poole into space

Keir Dullea plays astronaut Dave Bowman, and Gary Lockwood is his colleague Frank Poole, two of the dullest space travelers this side of Jupiter. It’s left to the HAL 9000 computer to supply the missing “human” element. With William Sylvester as Dr. Floyd, Leonard Rossiter as Dr. Smyslov, Margaret Tyzack as Elena, and the flat speaking voice of Douglas Rain as HAL (no, it was not a takeoff on the acronym for IBM).

Kubrick hired composer Alex North to do the background scoring, but went with a more eclectic, pre-recorded classical soundtrack instead (Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra and Johann Strauss, Jr.’s On the Beautiful Blue Danube, are among the orchestral delights, along with works by Aram Khachaturian and Gyorgy Ligeti) to serve as a commentary on the loneliness and mysticism of space exploration; he also trimmed his epic of about twenty minutes of redundant footage due to excessive length.

While music is the focal point for many of the film’s most impressive sequences, the most moving episode of all is also the simplest: a despondent HAL intones a little song in his final moments of life: “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer, do… I’m half crazy… all for the… love… of… you…”

Despite the director’s penchant for authenticity, the scene of the scientists inspecting the monolith on the Moon drew criticism from, of all people, the original scenarist Clarke, who claimed the men were not bouncing around on the surface as they would normally be in life — so much for realia on the big screen.

It’s on nearly everyone’s top-ten list of the best films ever made, and continues to exude a strong influence on modern movie-makers, to include Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott, and J.J. Abrams. Each successive generation finds new meaning in the work, and with reason. No matter how one feels about 2001: A Space Odyssey, it’s still the ultimate trip worth taking.

Copyright © 2015 by Josmar F. Lopes

You must be logged in to post a comment.